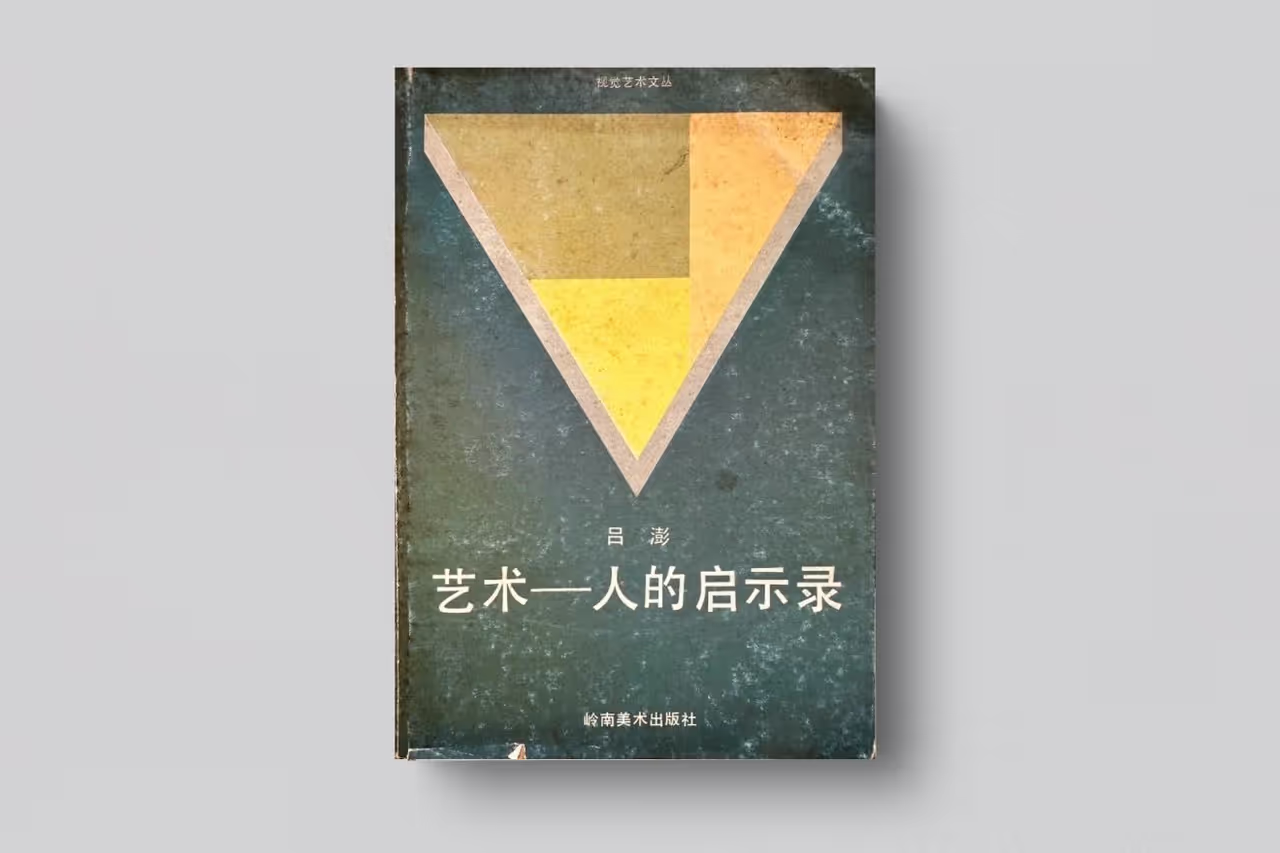

"Art—A Revelation of Humanity" could be considered the conclusion of a phase in my writing. The rampant essentialist moralism in this book reaches its peak. When I reread it, I found its centralist tendency of calling for essential truth to be quite overwhelming, almost unbearable. From the table of contents, it appears to be a thorough examination of various issues in art. I attempted to apply the knowledge gained from years of study, translation, and writing to a systematic analysis of these artistic issues. This seems somewhat ambitious, but in reality, there isn’t much difference in academic thinking compared to before. I still adhere to a vague, almost religious essentialism, believing that art is merely a reasonable expression of what is called "love."

But what is "love"? How can "love" become a tangible fact that people can grasp? If "love" can only be comprehended by those who already hold it in their hearts, then what does expression mean? If expression is meant to inspire others to approach or understand "love," then what is the criterion by which we acknowledge such expression? Can our knowledge truly provide us with a basic introduction? Are the historical facts of words really so passive, exerting no imprisoning effect on us? Does the ideogram for "love" always possess such profound meaning? Under what time, place, context, and whose usage does "love" hold a more positive significance? And at other times, places, and in the hands of other writers, does it not become a pretext for deception, boredom, or narrow-mindedness? Even if "love" and happiness are undoubtedly our ultimate goals, do we not need strategies to approach this goal? Should we truly believe that goodness can achieve everything?

Looking back, must we logically analyze cultural facts? Are various cultural facts inherently interconnected? Or can we consider that "connection" is merely a purposeful strategy of human post-phenomenon interpretation? If this is the case, should we examine our intentions? Ultimately, how do we clarify the scope of these intentions? And what does "meaning" mean? These questions are only a part of a larger set of problems. It seems that, in the work of the foreseeable future, we may need to start from a very specific "small" issue. In other words, the period of large-scale, macro studies and problem-solving has come to an end (although this can also be seen as strategic). We must embark on a project to deconstruct essentialism, and perhaps in the end, we will return to God. But for today, we do not discuss such un-discussable matters. This is the basic rule of academic advancement.