In late 1993, as the follow-up work for the Guangzhou Biennial came to a close, I headed to Shenzhen.In a special issue on art in the Border Trade News, I read an essay entitled “Artists Return from VeniceDisappointed.” The essay gave a basic introduction on the situation of the thirteen Chinese artists who tookpart in the Venice Biennale for the first time, and as the title suggests, these artists were perhaps less thanpleased with their experience there: the installation time was too short, the exhibition space was very subpar,the accommodations were lousy, most of the artists had to pay for their own travel, Chinese representative LiXianting had no opportunity to introduce Chinese art to the world, et cetera. At first, “Obtaining passportswas easy, and there wasn’t any trouble applying for Italian visas, and so these not-so-famous artists withdrewmost or all of their savings from bank and set off on a pilgrimage to this world art mecca with excitementin their hearts.” Their experience in Italy, however, did not live up to their rosy expectations. Though thisessay was statement of a school, and could not provide more detailed information, we did not have any othermaterial that suggests the artists who attended this large international art exhibition were either happy orsatisfied.

To be sure, the essay was a bit satirical, and in fact, Chinese contemporary artists did not live nearly aseasy twenty years ago as we would like to imagine. Not long before, due to the events of June 1989, manyartists and critics left their homeland. Most of them perhaps believed that only by going to Western countriescould they continue to develop in their respective fields. The artists and critics who remained in China didnot revive their spirits for a long time. Though younger artists, such as Fang Lijun, and some of the morevibrant artists of the 85 New Wave Movement, such as Wang Guangyi, restored their definitive artisticpractices relatively quickly, most artists continued to wallow in bitter meditations on the future of life andart. Here is what Zhang Xiaogang wrote in a letter to Zhou Chunya written in September 1989:

After returning to the academy, twenty days have passed in the blink of an eye, and it seems Ihaven’t done anything proper in all this time. I studied for a week, listening to papers and lecturesevery day until my butt ached and my head spun. Of course, in the end, I fail to escape from it. Thesecretary’s staff made a few requests and I said my piece, making it through smoothly. I thinkabout you over at the painting institute; who knows how much more serious it is over there, no needto mention the Academy is being treated as a “major disaster zone.”

Those few short sentences present us with the basic political context of the time. By the logic of any normalperson, leaving such an environment would be only natural. In a December letter to Mao Xuhui, however,Zhang Xiaogang leaves this record:

I got a letter from Yang imploring me to leave, and I plan to write back to tell him what I think. Ithink that, on the contrary, this is not the time to take flight, and it’s not about entering the “gypsycamp of Asia” either. Removed from the greater background of China, there is no “art” to speakof. As long as I can paint as I like, I will remain here…. The state I’m in these days feels a bit likereturning to the past. I’m listening to Beethoven and Tchaikovsky, with El Greco by my side, not tomention Sartre and Unamuno.

Whether or not it was by choice, most people stayed, but as spring approached in 1992, a certain set ofimportant modern artists, through constant pondering and provocative experimentation, was making theshift towards contemporary artistic practice. There is an instinct towards struggle in life, and when reasonis added to the mix, life can still create miracles. In fact, around the year of 1990, though modern artists hadno exhibition opportunities, another kind of release that was spreading through social life—the potential ofthe consumer market—gave artists a new opportunity to continue their work. In a June 1996 letter, WangGuangyi writes:

China is stuck in a war of words over the meaning of art, but this is pointless. From the absoluteperspective of contemporary mechanisms, only substantive success is real. Otherwise, no matterwhat we say to them, we are doing nothing more than establishing the so called illusory satisfactionof the cultured.

…Yet we also possess the ability to create “concrete myths,” just like the “snowball” abilitywe were talking about in Beijing. What matters is that we must ensure that this “snowball” trulyhappens, that it becomes a thing that the masses can perceive and puzzle over! If we do not makea big snowball, then perhaps others will make big snowballs. Perhaps the 1990s only needs a fewsnowballs. There’s plenty of “snow” on the ground, and we’ve got “stones” in our hands.Now we must actively roll up our snowball! Perhaps the times and history can only give us this onechance, and if we miss it, we will regret it forever!

In the spring of 1991, a strategic magazine was published under the title Art & Market. The first issue was onWang Guangyi, and in answering a series of questions from the editor, he said:

At present, Chinese contemporary art has not gained a status commensurate with the academiclevels it has attained. The reasons behind this are quite complex, but one main reason is that thereis not a powerful national bloc to back it up. The success of postwar American art is actually thesuccess of the national bloc. Otherwise, artists such as Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning andJasper Johns would not be what they are today. You used the term “art industry,” and that is avery good term. It touches on an issue of circulation. I think that we must first take part in thiscirculation if we are to be significant on this track. We have already begun taking part now, and Iwould predict that in five years, China’s “products” will be playing a decisive role in the worldart industry.

At that time, no one could have imagined the fate that was in store for Chinese contemporary art in the“world art industry” five years down the road, but through the efforts and liaisons of Kong Changan, wespent over CNY 30,000 to invite Flash Art editor Francesco Bonami to the “Guangzhou Biennial” heldat the Guangzhou Central Hotel in October 1992, in hopes that international society could learn about localChinese contemporary art. In that year, Wang Guangyi’s Great Criticism: Coca-Cola was featured on thecover of Flash Art (Jan-Feb 1992, volume 162), and I placed an advertisement for the Guangzhou Biennial inthe same issue.

In fact, Chinese art critics were already making efforts to promote international understanding ofChinese modern and contemporary art at that time. Before June 1993, Chinese artists and critics weretaking part in many art exhibitions. In 1987, Zheng Shengtian, Huang Youkui, Dai Hengyang and ShenRoujian were featured in Beyond the Open Door: Contemporary Paintings from the People’s Republicof China at the Pacific Asia Museum in Pasadena, California; in 1989, Fei Dawei curated Chine demainpour hier in Pourrières, France, and assisted Jean-Hubert Martin in organizing Magiciens de la Terre inParis; in 1991, Leo Ou-Fan Lee and Zheng Shengtian worked with the Pacific Asia Museum to create theexhibition I Don’t Want to Play Cards with Cezanne and Other Works: Selections from the Chinese NewWave and Avant-Garde Art of The Eighties; in 1992, Hanart TZ Gallery took part in a satellite exhibitionat Kassel documenta, and Kong Changan helped put together Cocart Bevete Arte Contemporanea inMilan; in early 1993, Andreas Schmid helped organize the China Avant-Garde exhibition in Berlin, whileLi Xianting, Johnson Chang curated After 89: New Art from China in Hong Kong and Mao Goes Pop inSydney. Domestically, historically important exhibitions organized by Westerners included the Liu Wei soloexhibition that Francesca dal Lago held in her home in 1990, as well as the exhibition of works by Liu Weiand Fang Lijun that she held at the Beijing Art Museum; meanwhile, the Beijing Diplomatic Staff Club heldthe exhibition Recent Works—Paintings and Installations by Zhang Peili and Geng Jianyi in 1992.

Nevertheless, as the Cold War drew to a close and the world entered into the post-Cold War era, theinfluence of Chinese contemporary art in the international community was infinitesimal for a long time, eventhrough 1993. At that time, artists in China had few opportunities to exhibit their works, let alone sell them,and at my urging, Wang Guangyi and Zhang Peili sold some of their important works for very little moneyto a friend of mine who had started a company. Before June 1993, no one had a clear picture of what theythought would come in the future, but they did have faith in art. The ideas, content and expressive forms ofChinese contemporary artists, however, were completely incompatible with the demands of the official stateart apparatus. Though Gao Minglu and other critics were able to hold the China / Avant-Garde exhibition atthe National Art Museum of China in Februrary 1989, this last hurrah of 1980s modernism did not imply achange in official standards for art, let alone the birth of a new art system.

Afterwards, modern and contemporary art would have a hard time entering into this shrine to thenational arts. It was under these circumstances that community-based elements of society began their supportfor contemporary art. The Guangzhou Biennial became a reality through the reaffirmed legitimacy of themarket economy and through community support. After Deng Xiaoping’s “Southern Tour” of 1992,anyone with a hint of political sensitivity could see that the market economy was clearly transforming thisnational art system. While official art organizations were wholly unsupportive of contemporary art, themarket, through its basic nature and functions, began the construction of a new art system, except that whenthe market first began to intervene in art, most people did not take notice of this decisive event. In fact, Ipointed this out in the foreword to the Guangzhou Biennial:

This “biennial exhibition” is unlike any other past exhibition in Mainland China. In terms ofeconomic backing, the “sponsorship” of the past has been replaced by “investment”; in termsof operations, the cultural organization of the past has been replaced by a company; in terms ofprocess, the administrative “notices” of the past have been replaced by legally binding contracts;in terms of academic underpinnings, the old ad hoc, artist-run “artwork selection teams” havebeen replaced by jury committees run by art critics; in terms of goals, the old monolithic, narrowand always argumentative goal of artistic “success” has been replaced by efforts towardscomprehensive economic, social and academic “effectiveness”…

The increasing penetration of the reform and opening policy has brought new changes to themethods of history composition. As the old standards have become unsuited to the needs of a newera, the importance of a new standard is becoming increasingly apparent. The central implication of the new standard is that culture must be produced for sale, a tenet directly aimed at the classicalmodel of “culture created for the sake of culture.” This is in complete opposition to the oldcultural production models of “self-indulgence” or political utility: it requires the support ofa series of contemporary market mechanisms such as laws, taxation, insurance and the furtherdivision of labor. For a country with no market traditions, this is truly an immense and complexundertaking, and the participants of this biennial exhibition—entrepreneurs, critics, artists, editors,even lawyers and reporters—have begun the task of confirmation and explanation required for theestablishment of the contemporary art market through their participation. Now, more people areclear in the understanding that in the 1990s, the question of the market is a question of culture.

To be sure, due to the rules of circulation and value exchange in the market economy, the contemporaryartists who were unable to gain official organizational support at home met the necessary conditions tobe brought into the international community by Westerners (including Johnson Chang, who lived underthe capitalist system in Hong Kong). Those Chinese artists who already lived and worked in the capitalistcountries of Europe and America, such as Huang Yongping, Xu Bing, Gu Wenda, and others who emergedlater such as Cai Guoqiang, also strove within their own unique contexts to take part in internationalexhibitions and became immersed, to varying extents, into international art circles. Over a period of time, artcritics such as Hou Hanru and Fei Dawei, well versed in the rules of the game in the West, gradually gainedthe status of “international curators,” and whenever they had a chance, strove to insert new Chinese artinto international exhibitions, placing it directly in exhibitions such as the Venice Biennale.

Regardless of people’s views on Chinese artists’ participation in the Venice Biennale, it was in factthe participation of everyone who cares about Chinese contemporary art that gradually led to the world’sawareness of Chinese contemporary art. More importantly, events, money and influence will changepeople’s views about Chinese contemporary art: in 2000, the Shanghai Biennial began using a curatorialsystem that approached the ones used in the West, and many Western artists took part in this exhibition; by2003, the Venice Biennale had a China pavilion, and though the presence of Chinese contemporary art atVenice was affected by the SARS epidemic, the establishment of this pavilion demonstrated that official stateart organizations had begun utilizing Chinese contemporary art in their strategies. The legitimacy of Chinesecontemporary art arose against this backdrop.

Moreover, while Chinese contemporary art still lacked the legitimacy of systemic protection, peoplecame to discover the serious influence of the market over art, and began to grow skeptical of Chinesecontemporary art in the market. Criticism of the relationship between Chinese contemporary art and themarket was also raised by certain Westerners at the same time. All of these critics should know, however, thatsales, capital and profit have been chasing the tail of the Venice Biennale since its first installment. Exceptfor the “storm” of anti-capitalist sentiment and protest that swept through several European countriesin 1968, capital and the market have never left art. In addition, the question of the market has specialcircumstances in China—since the 1990s, the only support for Chinese contemporary art has come fromthe market and the international resources that it brought. Due to certain complex political factors, Chinesecontemporary art is still far from establishing a scientific market system, and fundamental changes have yetto take place in the Chinese art system. Authority in the art field has not seen rational application because ofthe emergence of the market; to the contrary, the abuse of authority and crude market games have togetherproduced the conundrum that Chinese contemporary art faces today both at home and abroad. Since theeffects of the economic crisis first became apparent in 2008, the fate of Chinese contemporary art has alwaysbeen on everyone’s minds: how should Chinese contemporary art develop?

As I see it, artistic creation—antiquated as this term may be—is always a question for artists, Whenit comes to us critics, curators or historians, we can engage in reflection, rearrangement and evaluation oneverything in the past artistic trajectory. The artists and critics who have participated in the Venice Biennale have been full of anxiety, stress and questions, but I also believe that the artists and critics who have takenpart in this biennale also have unforgettable perceptions and stories, and it is through these perceptions andstories that our history of the event is constructed. Moreover, the global “historical passage” that began in1993 was not only Chinese contemporary art history but an integral component of global art history.

One day in 2011, Richard Widmer, an American who has lived in China for many years and deeplyunderstands Chinese contemporary art, sought me out at Café Copy in Beijing. He said that he wanted to doa research project on the Chinese artists who attended the Venice Biennale, and needed funding (roughly400,000 CNY). I agreed without hesitation. When I returned to Chengdu, I worked out an idea: wouldn’tit be more complete if we held a retrospective on the historical exhibition of Chinese artists at Venice,combining historical documents with their recent works? As a result, Chengdu Museum of ContemporaryArt provided one million CNY in funding to collect the relevant historical material and research work forpublication. At a time when there are many exhibitions every single day (while in the past, for instance in1995, there were very few opportunities for the exhibition of modern and contemporary Chinese art; in 1996,Huang Zhuan planned a valuable contemporary art exhibition at the National Art Museum of China, entitledFirst Contemporary Art Academic Invitational, but it was forced to shut its doors on the eve of the opening),the older generation of critics are stepping back from the center stage of history, while most new young criticsare becoming curators, as immense economic pressure makes it difficult for them to promote academicresearch. Of course, research on contemporary art still rarely gains support from official art organizations,and this situation forces us to continue seeking strength from the community so that we can prepare the basicmaterial that will be needed by future art historians. I have already completed 90s Art China 1990-1999(published in 2000), and in the spring of 2012, A History of Chinese Contemporary Art in the 21stCentury2000-2010 (published in 2012), and the composition of these two art history texts has made me acutely awarethat the twenty years of Chinese contemporary art history must be researched from multiple angles. And so,at this time when the entire contemporary art scene is engaged in reflection and retrospection, I think thatthe twenty year history (1993-2013) of Chinese artists participating in the Venice Biennale is an importantangle for historical research.

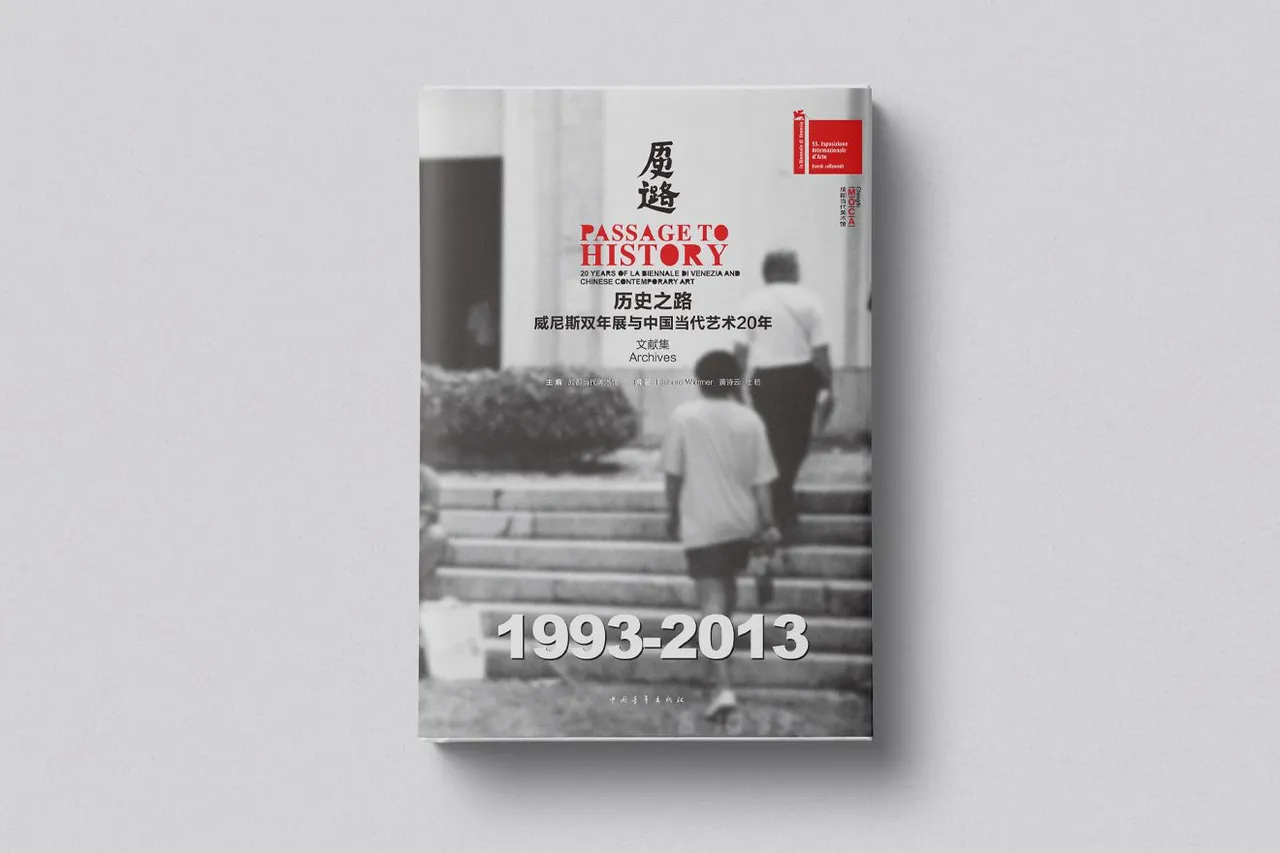

For most of 2012, Richard Widmer and his assistant Huang Shiyun traveled to many cities, visitingnearly all of the artists who have participated in the Venice Biennale over the years. This work has providedus with primary material on those artists and their participation in the biennale, which is now beingpublished under the title Passage to History: 20 Years of the Venice Biennale and Chinese Contemporary Art(Interviews). The book brings together interviews of over 70 artists and other participants who have takenpart in the exhibitions, as well as documents pertaining to Chinese contemporary art and the Venice Biennalesince 1993, providing the reader with a rich trove of materials. Meanwhile, many historical documentsprovide us with photographs and sketches pertaining to this period of history. When we read about the pastthoughts and experiences of these artists through these textual and visual materials, it is hard to contain ouremotions. Through the careful compilation carried out by Widmer and his team, we have also publisheda catalogue rich with images. Actually, after reading these materials, we can clearly see that it was thecombined efforts of Chinese contemporary artists and critics at home and abroad, as well as those Westerncurators with a passion for art that made this precious period of Chinese contemporary art history possible.In order that today’s readers and viewers can quickly gain an understanding of the history of Chinese artistsat the Venice Biennale and learn about the historical nature and role of the Venice Biennale. I have askedChina Academy of Art graduate student Wang Yang to compose Passage to History: 20 Years of the VeniceBiennale and Chinese Contemporary Art, aimed at younger readers in order to inspire them to research andpay attention to Chinese contemporary art. In this era flooded with material desire, as history prepares toturn a new page, the research of past history by young researchers is both necessary and highly significant.Of course, we have also compiled and published a catalogue for this exhibition. Many of the artists includedin this exhibition have attended past installments of the Venice Biennale, but we have also selected a few who have not. We have also selected one young artist to take part in this exhibition to show that Chinesecontemporary art must be both rooted in the past and facing the future in a continuous line of development.

Unlike previous Venice Biennale exhibitions, this exhibition will be presented simultaneously in bothVenice and Chengdu. The Venice space will be at the Arsenale, Nappa N.89 and the Chengdu space will beat the Chengdu Museum of Contemporary Art. There are several reasons for this decision. The first is thehope that the Chengdu residents who are unable to travel to Venice can see the Passage to History exhibitionfor themselves and gain a synchronous understanding of the historical information. Chengdu MOCA’sact of bringing leading Chinese contemporary artists to the Venice Biennale is an important cultural eventfor the city, and we of course must try our best to allow the people of Chengdu to take part. Second, the“Passage to History” is not merely the historical progression of Chinese contemporary artists at Venicebut the historical progression of Chinese art taking part in the composition of global art history, and wecan reexamine this controversial and uniquely valuable history from a new perspective. Chengdu is a citywith rich contemporary art traditions that provides the proper climate for the presentation of this “Passageto History” exhibition. Third, the year 2013 will see the sixth installment of the Chengdu Biennale, and Ihope that the warmth of the Venice Biennale, which opens in June, can be carried on in Chengdu, serving asan artistic and historical wellspring for this year’s Chengdu Biennale. In September 2011, Venice DeputyMayor Tiziana Agostini travelled to Chengdu and praised the fifth Chengdu Biennale, and the year 2013should be a good opportunity to further promote the cultural and artistic exchange for these two cities, sothe establishment of an exhibition venue in Chengdu will help to promote this exchange. Coincidentally, theopening of the “Passage to History” exhibition in Chengdu will coincide with the commencement of theFortune Global Forum in Chengdu, and global economic and political leaders will have a chance to learnabout the international character of this city: internationally influential artists and an exhibition will provideattendees with artworks of the highest artistic caliber, clearly providing much spiritual wealth to these peoplewho have come to discuss the material wealth of nations. And, in a touch that I’m sure will prove interesting,we have created a visual channel for live interaction between the Venice and Chengdu venues, so thataudiences in both places can see the same exhibition taking place in two locations in different countries andhave the chance for a broader exchange.

Finally, I would like to thank Achille Bonito Oliva. In bringing Chinese contemporary art to Venicein 1993, he got the world interested in Chinese art and the destiny that stands behind it. I spoke to Oliva inearly spring 2012, saying, “When you first brought Chinese art to Venice, it had a huge impact in China.Some Chinese critics chimed, ‘Oliva is not the savior of Chinese art.’ How do you feel about that?” Hereplied, “Of course, I’m just an Italian who loves art.” This left a deep impression on me. We reachedan agreement to co-curate Passage to History: 20 Years of the Venice Biennale and Chinese ContemporaryArt, and agreed to each write an essay, no less than five pages long, commemorating this period of history.I would also like to thank Paolo de Grandis. The assistance of his organization smoothed the path for thisexhibition. In addition, I would like to thank the staff of the Chengdu Museum of Contemporary Art and allother members of the team. It would be difficult to imagine such a comprehensive and professional exhibitionand publication without their dedicated efforts.

February 11, 2013

Fairy Tree Courtyard, Chengdu