The plane departed for Rome – my fourth trip to Italy over a year.

After a period of preparation driven by complex impulses, the exhibition I curated finally opened at MART, the acronym of Museo d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea di Trento e Rovereto, known in English as the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Trento and Rovereto. This was the first stop for the exhibition titled Global Painting: A New Generation of Chinese Artists. The participating artists were all young people born in the 1980s and 1990s, and my aim was to stage a traveling exhibition of young artists that would move through Europe, both to satisfy my curiosity and thinking about the iteration of art in recent years, and to introduce new Chinese art abroad. At some point in the preparation of the exhibition, I found my motivation and approach somewhat at odds. When the pandemic was about to hit, I was busy writing A History of China in the 20th Century, and at that time, I seem to have entered a mental space that went far beyond the scope of my concern for art history, and I then felt quite hesitant about ever writing anything more about art history in the future. On 7 June 2019, I finished writing my article "Disappearing Cozy Moments: The Transition from Writing Art History to Historical Writing", following the invitation I received from Jin Ning, the editor of Literature and Art Research, to write something for his journal. At the end of the resulting article, I wrote:

With the study of art history, especially the history of modern and contemporary Chinese art, I have become more and more interested in history and not just art history, and because I often read the relevant theoretical works of the history of historiography, especially the new historiography, I have become more and more convinced that the writing of history can also be regarded as a kind of literary writing based on factual materials, in other words, history is really shaped by us. However, the more I try to find contextual connections to specific artistic issues, the more deeply I look into those contexts, and this approach eventually led me to ponder increasingly the historical events that took place and the issues that unfurled in the 20th century itself. As a result, the cozy times I spent writing art history disappeared, as I embarked on writing the weightier History of China in the 20th Century, and as I searched through articles I had previously published in Literature and Art Research at different times, I noticed that my eventual and inevitable turn from art history to historical writing had in fact been prefigured much earlier.

In "Disappearing Cozy Moments", I explained in detail why I started to write historical works that go beyond the scope of art history. I was well aware that my inner drive to devote so many years to writing art history expressed my desire to acquire a deeper understanding of historical issues that are not limited to artistic language, style, and mode, and the mood of that time seemed to demand that my art history writing should be over. In "Disappearing Cozy Moments", I also confessed to having donated more than 2,000 reference books on the history of modern and contemporary Chinese art to the Chinese University of Hong Kong. I recall that when I completed History of Contemporary Chinese Art: 1990-1999 in the early spring of 2000, I had quietly bidden farewell to art history writing, but at that time, because of the need to earn a living after falling on hard times having lost the salary I received from the Federation of Literary and Art Circles and needing to support my family. However, now I felt, for personal reasons, that I really had to cease writing art history.

Once again, this was not to be the case. However, over these years I was never able to let go of the mental obsession that had troubled generations of scholars―to write and publish a “history of China.” In fact, I had first embarked on writing a "preface" for such a book in 2013. However, only when I saw for the first time the two thick volumes of my A History of China in the 20th Century on the table in front of me in a café in Milan at the end of September 2023, was the uneasiness and anxiety in my heart finally relieved. I have to admit that even when I had published my own art history books in Italy, France, and South Korea, whenever I saw these volumes for the first time, I did not feel any emotional excitement; their publication simply seemed to be the logical end product of my own writing. The publication of A History of China in the 20th Century made me ask: what would I write in the future?

2023 was a turning point for me. When I was in London on 16 October 2022, I still felt anxious about finally completing the book, but a few days later I wrote the last paragraph of Chapter 10 of A History of China in the 20th Century in Milan. In Europe's fashion capital, I was in a relaxed mood when I visited Max Ernst's retrospective at the Palazzo Reale Milano, and I recalled the different times when I had seen systematic and professionally researched retrospectives of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Carlo Carra, and Giorgio de Chirico in that city. On this trip I also had the rare opportunity to see the systematically presented exhibition of original Italian modernist works in Milan’s Museo del Novecento. After that, I went to Rovereto with my designer friend Yin Jiulong to visit the MART collections and again see works of the Italian modernist period. In Spain at the beginning of November, Huang Mei in Spain took us to Girona, an old town not far from Barcelona, where we enjoyed coffee in an outdoor café and visited the old buildings and streets. In fact, in the last quarter of 2022, I visited museums in more than a dozen cities in the United States and six countries of Europe, and the visual experiences along the way brought back memories of my early years studying art history. From the Renaissance period of Italy, I saw a large number of works in museums in Spain, Germany, and the Netherlands. In London, I saw Hans Holbein the Younger’s painting The Ambassadors, which had made a deep impression on me when I was translating a book treating the art of England. In Berlin's Neue Staatgalerie I saw a comprehensive exhibition of expressionist works, many of which I had seen only in art history volumes. In addition, two experiences in Europe over the years confirmed for me that, even though In China in the early 1980s we could only study Western art history through poorly printed books or albums, this experience nevertheless proved useful and meaningful: One occasion was in the Prado in Madrid, where on the far wall of a large exhibition hall, I recognized a painting of a dwarf sitting at the side of a road by Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez, which had appeared many years earlier in a small black and white volume published by the People's Fine Arts Publishing House, and another was when I saw a painting in the collection of a church in Napoli, which I immediately recognized as a small landscape by Poussin, recognizing his composition, technique, style, and atmosphere from a print of his work I had seen in a Chinese book. I would like to say that in the past, although we did not have the excellent conditions to see original works of European art as we do today, the reading of low-quality printed materials published in the early days of reform and opening up, as well as the translation of the few original works of art history, still made me feel the breath of another civilization in my early years, and cultivated my visual experience of art history. In fact, when my first book on Western art, Modern Painting: A New Figurative Language (reprinted in 2022 under the title A Brief History of Modern Painting in Europe) was published in 1987, I had not yet been able to go abroad to see the original works, except for some prints by Edvard Munch, which I saw at an exhibition in Chengdu in the early 1980s. I did not have the opportunity to see original works of European artists, but the few reproductions of original works and drawings that I occasionally saw in English language books I read and perused must have conveyed a lot of information about art history and nurtured fairly useful visual memories for the future, which in turn also inspired me to write about the history of painting in the context of another civilization without seeing the original works.

As 2023 draws to a close, I have spent this year completing the English revision of A History of Chinese Art in the 20th Century (Macmillan wanted to change the title of the book to A History of Chinese Art in the 20th and 21st Centuries because it deals with artistic phenomena from 2000 to 2020), and at the end of the year, a revised edition of the Italian version of my The Story of Fine Arts was published by Rizzoli, so that it seemed to me that one of my writing phases was over, and I should think about the theme of my next book. After the opening ceremony of Global Painting on 6 December, we traveled to Milan, Florence, and Rome. The El Greco exhibition at the Palazzo Reale Milano, the Giotto and the 13th Century Exhibition at the Uffizi Gallery, and the Botticelli and Renaissance Florence in the Uffizi space once again washed my visual experience, and I especially noticed that the differences between the styles and techniques of Botticelli's works from different periods raised a lot of questions in my brain. From one room to another, I paused to gaze at the works of the great artists, and even though I had visited the Uffizi Gallery many times, it still constantly enchanted me, aroused my curiosity, and filled me with nostalgia. Every time I looked at these works, they raised new questions.

Given this experience, would I continue to write about history at a remove from art history with the same degree of urgency I felt during the three years of the pandemic? I would like to say that since I returned from Europe in October this year, I have found that my interest and love in art, especially the study of art history in my early years, encouraged me not to give up exploring the knowledge of art history. Indeed, I love art history, and I also realize that in today's special historical period that has been filtered by reform and emancipation of the mind, art and its history can still provide me with a great deal of space to think and write freely, not to mention that art history not only brings us knowledge of the history of art, but is also a way for us to understand human nature and gain insight into spiritual issues. In May of this year, I visited the Villa I Tatti for the second time. I learned more about this library and institution for the study of Renaissance art history when I proofread Lü Jing's translation of James Stourton’s Kenneth Clark: Life, Art, and Civilisation, and the story of the two art historians, Bernard Berenson and Kenneth Clark, inspired me to visit Villa I Tatti for the first time when I visited Florence in October 2022. Villa I Tatti's library and gardens, which have remained largely unchanged for a century, imbued me with a deep sense of civilization’s nurturing and eternity. This atmosphere inspired me to spend two days in a small guesthouse nearby during my visit in May so that I could properly imbibe more of I Tatti’s atmosphere. Indeed, for me, visiting such a "holy place" not only entails a complete academic investigation, but also a remembrance of Renaissance humanism. I know that few people in today's contemporary art circles are interested in ancient history that is far removed from contemporary art. Some even think that ancient art has nothing to do with contemporary art, but isn't this how we came to be what we are today?

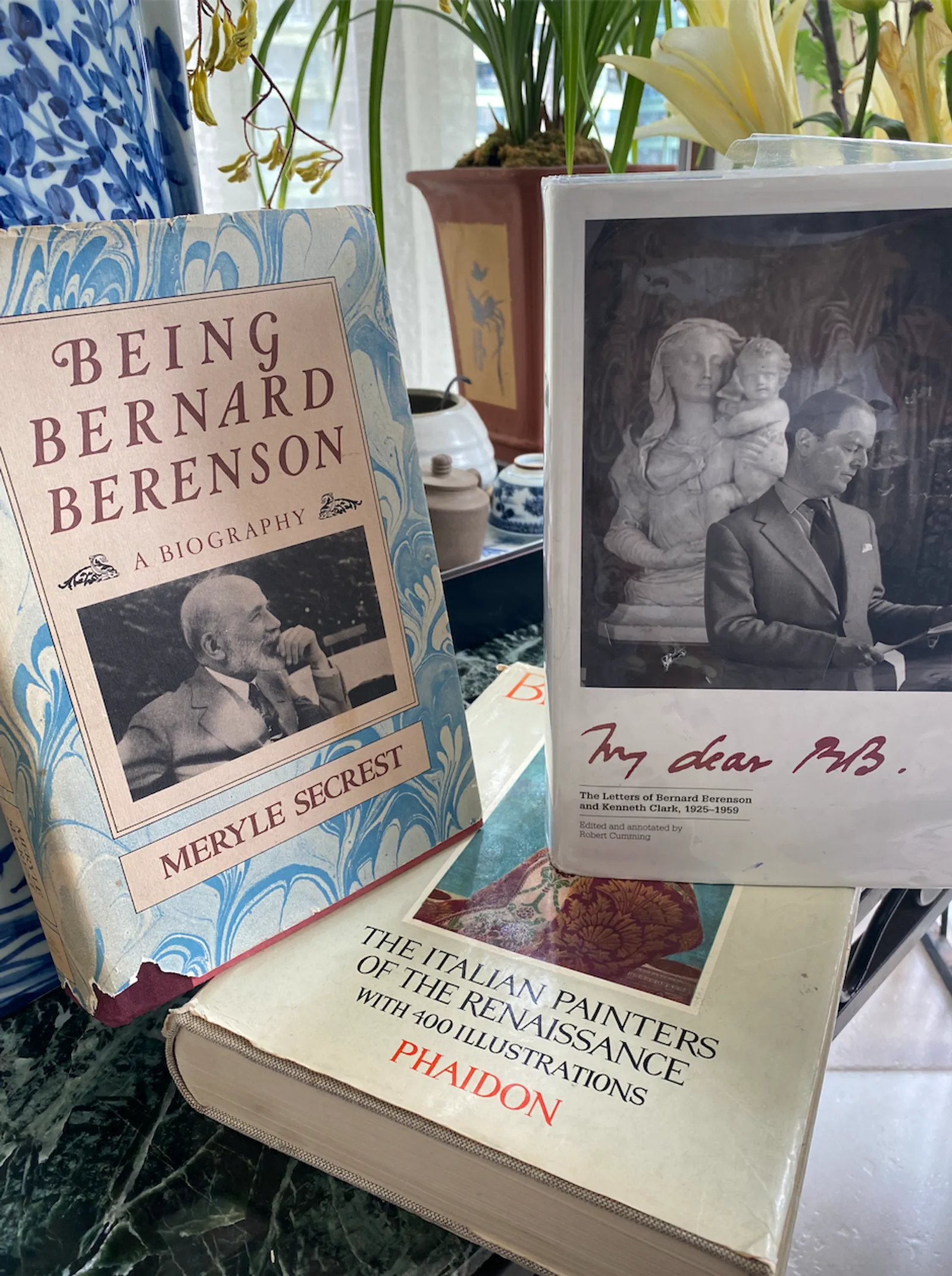

In the middle of the year, Zhang Min, who had been a graduate student in the United States and later went to Peking University to study for a Ph.D., brought back three books from London: Berenson's famous work Italian Painters of the Renaissance, My Dear BB…: The Letters of Bernard Berenson and Kenneth Clark, and Meryle Secrest’s Being Bernard Berenson. In Western art history circles, these books are not at all fashionable like works by Timothy J. Clark or Hans Belting, but they are no less scholarly for students and teachers trying to understand the history of art and its historiography in the English system, so I wanted to translate Being Bernard Berenson. My experience of visiting art museums in European cities has indeed restored the psychological interest I felt for studying art history in my early years. When I reflect on writing of A History of China in the 20th Century over the past few years, it is indeed related to a specific political context and the stimulus of events—the writing of this history was the result of the early thinking and social atmosphere experienced by people born in the 1950s (a generation that cares about the grand narrative of society and the fate of the country). However, those who have experienced the more than four decades of complex historical changes since 1978 should reflect on themselves: Have we not yet realized that the power of the individual is indeed insignificant in the long course of history? Could it be that the cultural and ideological inertia of thousands of years can be easily destroyed by decades of development of material forces? Is it true that the value of an individual's existence can only be presented within the framework of a grand narrative? Is it true that the spiritual world of the individual cannot effectively survive in a very narrow space of interest? Of course, the most basic question I feel is: how can we find a place and opportunity to settle down in our daily lives, when we receive increasingly negative, uncomfortable, and even bad news, without compromising with fate and bowing to the forces of evil?

Everyone's time, experience, and ability are extremely limited, and attitudes towards life is completely different after all; aware of such a problem, it seems that we should stop trying to infinitely touch the impossible "ceiling" of life. In fact, for a writer, the "ceiling" of life is to do our best to experience and understand civilization in daily life, and write out our own experience, and communicate with others through publication or online. Based on this understanding, I soberly decided to continue writing art history in the coming days, and try to engage in some art history translation in my future writing journey. Recently, I also thought that although the capabilities of AI seem very powerful today, the intrinsic nature of humanist words cannot be explored by literal and routine translations. "Inner needs", a term for the inexplicable used by Wassily Kandinsky very early on, determine people's ability to judge, just as human beings have developed from primitive society to today's civilized society, even if artificial intelligence produces a new species, its own logic will also derive corresponding ethics and morality, and extend the positive forces of human civilization. I continue to believe that the future of humanity is based on good, and that the future will produce new elements of control that will give humanity the conditions for survival and development. Of course, people's happiness is not only limited to expectations about the future, in fact, happiness itself can be achieved only in reminiscing and thinking about the past. In any case, it is enough to focus my days and energy on art history, and this was the natural change of mind I reached in 2019.

Written on Thursday, 30 November 2023 on a Chengdu – Rome flight and revised on 17 December 2023, on a flight from Rome to Chengdu.