Yue Minjun: The Story of the Smiling Faces

A preoccupation with destiny is a demand made by life, but we can never know fate’s outcome. Those who follow auction salesroom figures might be familiar with the red beaming face that is now an icon, but never connect the Yue Minjun of today with yesterday’s Yue Minjun. The laughing and joking beaming red face is an icon, but it lacks direction; like Andy Warhol, when asked where Pop’s going, the answer is ‘I don’t know’. A fixed icon or image can exert enormous influence, and not only summon up vast sums of money. Many years ago, Yue Minjun was looking out at the boundless sea from an ocean oil drilling platform and contemplating an unusually hazy life. At that time, who could see what future miracle awaited this ordinary laborer? Life is inevitably influenced by its irreversible context, and those different experiences and opportunities influenced Yue Minjun’s growth and produced his art. If you investigate an artist’s experiences and the characteristics of his thought, then any judgmental conclusions about what is ‘inevitable’ or ‘accidental’ will probably be wrong.

Yue Minjun was born in 1962 in Daqing city, Heilongjiang province, a city built up after the discovery of oil there in 1959. Yue Minjun’s memory was formed by the difficult life and bitter cold winters in that frontier town. For a long period, Yue Minjun was constantly on the move with his itinerant parents:

In 1966 our family was reassigned to the Jianghan Oilfields in Hubei .. When we all moved to Hubei, I saw a lot of street fighting and some hotels add machine-gun emplacements out the front. It had not seemed that terrible in Daqing, which maintained its economic growth, but after we left, things completely changed. The deepest impression in Hubei was Wuhan, and the hotel in which we lived had antiaircraft guns inside, and there was some fierce fighting. [1]

Going through primary school Yue Minjun started at a rural school in Hunan. Two years later, he went with his family to Beijing. Yue Minjun was educated during the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution, and the turmoil on the streets and the constantly changing teachers made his education quite different from that of youngsters in a stable social environment. After graduating from high school, Yue Minjun was sent by his parents to the maritime petroleum in Tianjin. There he found himself involved in ‘repetition’, a characteristic of his later art work:

My work was on an oil drilling rig. I would work for 20 days and rest for 20 days, and I would go there and leave either by helicopter or towboat. I worked on the rig for three years, facing the ocean and seeing nobody. There were only men and no women on the rig and to keep us psychologically calm, the unit would organize three girls to screen films for us each Sunday. Most of the old comrades made it their main purpose to see these three girls, and the films did not matter in the slightest. There were three screenings each day, with two films at each screening, morning, afternoon and evening, six all up. That was life. [2]

In such a working environment, Yue Minjun realized that he has lost his normal mental responses: ‘If someone was with you in that place or if they said you must leave, you could become abnormal, very abnormal’. [3] Three years later, he went to Huabei Petroleum in Hebei, and here he finally became an oil prospector. He felt unable to adapt to this environment: ‘From that time, I decided to take up painting and study it, and so I carefully prepared for the college entrance examination’. He was hoping to change his life.

Prior to this in 1977, Yue Minjun’s parents got him an old teacher who had been a professor of Chinese gongbi painting and calligraphy, and who later taught him basic skills and techniques, such as quick sketching, crayon sketching and watercolor. Perhaps, his time during high school sketching scenery outdoors in Yuanmingyuan made a deep impact on Yue Minjun, and the white birches and ruins there became subjects that moved him. Yue Minjun later recalled how he often saw Wu Guanzhong and other gentlemen out painting the scenery there:

Some of the Stars people made a big impression on me, and they were often there also painting the scenery. I remember a young guy, who was probably about twenty or thirty years old. He looked very handsome, painting landscapes. But he painted purple skies and pink trees, and everything he painted was unnatural. I asked why he painted like this, and he happily told me that this was a new understanding of art. We had seen all their many exhibitions, and most of their paintings were fairly abstract. There was another artist called Feng Guodong from Beijing who was about fifty or sixty years old and his paintings were even more abstract. They were the talk of Beijing and everybody was arguing about them. A lot of things that were fashionable during the ’85 New Wave were pretty similar to this work. You could also see impressionists, like Cezanne, abstract paintings like Mondrian and some US expressionist things. You could already see all this. [4]

At this time, there were great changes in the social environment, and the national working conference on artistic education in February 1979 refuted the earlier Gang of Four policy that art education was ‘a dictatorial black line in literature and art and in education’. In May, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China rescinded the Lin Biao and Jiang Qing line on literature and art, and restored the legitimacy of progressive literature and art of the 1930s and post-1949 literature and art. Progressive literature and art resumed and the legitimacy of literary and artistic work since 1949 was upheld. In October, the fourth national congress of literature and art workers of China was held in Beijing, and Deng Xiaoping delivered a speech on behalf of the Central Party Committee and the State Council of the Communist Party of China, in which he pointed out that there could not be flagrant interference in literary and artistic creation. Yue Minjun did not have any direct relationship with these political changes, and it is very difficult for us to judge whether he knew or cared about this kind of question. However, he enjoyed the freer social atmosphere that came with the changes. It was in just this atmosphere that Yue read Romain Rolland’s masterpiece Jean-Christophe when he was on an oil boat, but before 1976, such reading materials were deemed to be bourgeois and were forbidden. In any case, the members of the Stars were striving for democracy; at the same time Scar Art and Life-stream art (shenghuo liu) had emerged and the atmosphere in the world of art was changing. Artists were experimenting with grey mood colors and politically accusatory themes, and there was a break from the academy system that went back to the Russian art academician Pavel Petrovich Chistyakov (1832-1010). All these changes changed people’s visual habit, and young people studying art had taken the first steps towards freedom.

On the oil rig where he could only see the arc of the horizon, Yue Minjun had done paintings of the ocean and the changing skies. These pictures did not reveal that he would later become an artist, but the purity and transparency of the blue sky and the marine environment were visual genes that would appear later in Yue Minjun’s paintings. As we have already seen, the direct motive force that first made him want to become an artist was the strong hope of changing his living environment. In 1984 he was assigned to an especially arduous post, as a petroleum prospector, and he decided to get into university and quit that environment and life. This was a very important step. It was forced on him by the environment and his dissatisfaction.

In 1985, when various modernist art groups were beginning to emerge across China, Yue Minjun was admitted to the Fine Arts Department of Hebei Normal University. According to Yue, he matriculated to three colleges at that time: Hebei Normal University, Film Academy of Fine Arts and the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts, but he decided on the college in Hebei because it provided a stipend of 45 Yuan each month, which he felt would somewhat lighten the burden on the family and give him some freedom as well. At college, Yue Minjun not only received specialist training in painting, but he also managed to read a large number of Western works, including Taine Hippolyte’s The Philosophy of Art and Hegel’s Aesthetics, two works which provided him with key to understanding art and The Psychology of Art by E.H.Gombrich, which had a profound influence on him. These works increased Yue Minjun’s comprehension and judgment of artistic and related questions, and he said that he began to acquire a concrete understanding of abstraction and expression.

In fact, when Yue Minjun was studying at Hebei Normal University, the modernist ideological trend had already reached the school and, although it exerted no decisive ideological impact on society, it accompanied the liberation in philosophy, economics, literature and the other humanities, and subconsciously influenced people, although the ’85 New Wave made a somewhat more direct impact on the art world:

In fact before entering university I had met made some friends in the Stars group, and they naturally had a great influence on me. Fine Arts in China (Zhongguo meishu bao) had already started publication at that time, and I felt that modern art had to be much better than traditional art and I liked these things, such as Huang Yongbing’s Xiamen Dada and the experimental works of Wu Shanzhuan, Gu Wenda, Xu Bing and Wang Guangyi which seemed very rich and later opened up the visual field for art circles. That was the feeling we had at that time. [5]

However, the exercises Yue Minjun was given at school were classical, because the lifelike or naturalist traditions of realism were still deeply entrenched, but after 1986, people began to be influenced by the classical painting of the teachers of the Central Academy of Fine Arts. Because of the authority of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in the fine arts and for historical reasons, the painters advocating classical painting, such as Jin Shangyi, Yang Feiyun and Wang Yidong, were still influential, not only through their painting but also as teachers. Discussions during this period on the issues of the new academism and ‘purified language’ also blurred the field of vision. In October 1987, a master’s degree research candidate at the Central Academy of Fine Arts published his graduation thesis on ‘Neoclassicism and its Enlightenment’ in the journal Fine Arts (Meishu). He expressed his admiration for the artistic thought of J.D.lngres (1780-1867) and painters like him, boldly connecting classicism’s techniques and the vocabulary of tradition, concluding as follows: ‘Painting is a culture that is controlled by social and political factors, at the same time as it is still controlled by cultural tradition’. He made the point that many aesthetic concepts (richness, profundity, delicacy and fullness of spirit and form) needed reinterpretation. But, according to Yue Minjun, he himself did not have the energy to expend on painting classicist things and, within less than half an hour of painting, his pupils would dilate and his head feel faint. Yue Minjun at this time developed no particular concept of art of his own, even if his resistance to classicism was only physiological.

Unlike Fang Lijun who was one year younger than him, Yue Minjun had no contact with New Wave critics until 1989, when he graduated and became a teacher in the Fine Arts Department of the North China Petroleum Institute of Education. He did not participate in the China Avant-Garde exhibition in February 1989 in Beijing, to which Fang Lijun sent three sketches that clearly foreshadowed the direction of his later work. He only saw magazine reports and images from the show, among which Geng Jianyi’s Second State (Di’er zhuangtai) left a deep impression on him. This was not a simple impression about an art issue, and subsequent works and the emotions they expressed clearly reveal that we are seeing that Second State represents an early absurdity. In any case, such absurdity was very close to his everyday feelings, as were those repeated large aimlessly beaming mouths that people pondered. But wasn’t this his own feeling and manner? After June 1989, Yue Minjun was in the same state as most other artists; he felt ignorant, without goals and utterly uncertain about the future, but he kept on going even though he could not explain why he did so at this time. But, going from a relatively free student life to an environment in which he worked as a regular teacher was difficult, because he had already been influenced by modernist thought and the intolerable environment in the wake of the political turmoil of 1989 meant that Yue Minjun had to choose whether he worked or sought artistic freedom. Consciously or unconsciously, he found that teaching about books like Van Gogh’s biography Lust for Life made him feel the allure of art. Such myths about art stirred his yearning to become an artist and so he opted to pursue the possibility of freedom and life. Adopting a passive attitude, he arranged for leave from the school and left his workplace to go and find temporary lodgings in Beijing.

In 1990 Yue Minjun went to see the exhibition of oil paintings by Liu Xiaodong in the gallery of the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, which made a great impact on him. In Liu’s work he saw the possibility of depicting everyday life and feelings directly in paintings:

I remember seeing Liu Xiaodong’s exhibition in the gallery of the Central Academy of Fine Arts and his paintings touched me greatly. I think before this I felt painting was not interesting, too removed from my life and simply meaningless. When I saw his paintings I felt that they were closely related to life and the spiritual state of the country. I discovered you could express yourself through paintings. I was reading a novel at that time by Shen Congwen in which he mentioned ‘sticking to yourself to write’ and this meant getting back to your own feelings. So I started getting back to my own life; friends were closest to me so I began painting friends, groups of friends laughing and joking together, which was also a projection of my own psychological state. Later I went to Yuanmingyuan and visited Fang Lijun and Liu Wei, and I was also struck by their paintings. The absurdity of Fang Lijun taught me a lot, and Liu Wei’s directness and power to shock were impressive. [6]

This statement is significant, because while Yue Minjun learned his basic painting techniques at college and had been influenced by different styles of modernism, his own painting does not seem to have taken off until Liu Xiaodong and Fang Lijun showed him the possibilities of art and gave him the initial confidence required for his future development. Before Yue Minjun moved to Yuanmingyuan in 1992, many artists were already living there. Ding Fang, Fang Lijun, Yang Shaobin and Xu Yihui already had their own cottages and workshops in this desolate countryside. Far from government organizations and work unit management, and outside the metaphysical idealism of Ding Fang, the state of the individual lives in Yuanmingyuan is directly recorded in the works of the younger Fang Lijun and Yang Shaobin. Those works and the artists’ life style and psychological states were in harmony. This enabled Yue Minjun to directly savor the possibility of living and working as an independent artist. As early as 1991, Yue Minjun participated in the New Period Modern Painting Exhibition held at the Friendship Hotel and he made contact with a number of artists living at Yuanmingyuan, including Lu Lin, Yi Lin, Wei Ye and Yang Shaobin. In 1992, he severed all links with his original work unit and moved into Yuanmingyuan artists’ village. To begin with, he was poverty-stricken, and he has recalled how he and Yang Shaobin first shared a studio, and he would get through the difficult times by selling water-melon and pancakes at Peking University. [7] In that year, he participated in the Exhibition of Works by Painters from Yuanmingyuan held at the Yuanmingyuan artists’ village and this marked his real beginning as an independent artist.

Memory and daily life in combination often produce boredom and depression. In 1991, he painted The Comedy in the Unnamed City Gate (Fasheng zai X chenglou de xiju) and Crazy Laughter (Kuangxiao). Perhaps living in Beijing alerted him to real politics and The Comedy in the Unnamed City Gate was a work clearly set in the Tiananmen gate tower of Beijing. The title of the work was cryptic, in that an ‘X’ stood for the deleted name of the gate and the use of the word comedy to describe the work was ironic, because the painting depicted three expressionless and bored young people taking photos of each other playing with a puppy at Tiananmen. As in works of the 1980s that show difference, such as Ding Fang’s The Strength of Tragedy (Beiju de liliang) that expressed a sense of sacrifice and Mao Xuhui’s Human Bodies in Cement Room (Shuini fangjian li de renti) series with its suffering, the youth in the foreground with the gaping mouth is intended to show the complete casualness of the entire scene. Any person with historical context can see the historical significance of these young people on the Tiananmen gate tower who appear to lack any seriousness in an environment that calls for seriousness, yet the artist has blithely adopted a position that resists criticism. After more than a decade of liberated thinking, following the acceptance and study of Western thought in the 1980s, it would have seemed excessive to analyze this work using simple ideological criteria. After all, they are only laughing young people who have done nothing wrong. The composition is very important, because it reveals the direction in which the artist is placing his unconscious resources. Yue Minjun does not retain the visual authenticity that typifies the work of Liu Xiaodong, but he also wanted to depict the daily life of the friends around him. He was also unable to simply extract his self from the work and link it with elements of history, society and politics, as Fang Lijun succeeded in doing. Like Wang Guangyi he was sensitive to historical and political reality, but could not limit himself to present a critique limited to cultural questions. Yue Minjun was instinctively concerned with his own daily life, but unwilling to return to any of the techniques he had studied at college, and so the direction of his images is fuzzy and inclines towards metaphor. The young man in Crazy Laughter, who also appears in the composition of The Comedy in the Unnamed City Gate, is the image of a friend repeated several times in Unnamed City Gate, but although the toothy character does not appear to have special significance, but he soon becomes a basic pictorial leitmotif of the artist in subsequent works. He becomes the focus of paintings completed in 1992, including 1992, Big Ears (Da erduo), Big Savior (Da jiuxing), Great Unity (Da tuanjie), Untitled (Wuti) and Chinese Lanterns (Zhongguo denglong). The figure is not the artist himself and in other works, with the exception of Untitled, the figure provides a context for the images of various friends. Yue Minjun has provided the following explanation:

I added a lot of political elements to my work in the early 1990s, and felt compelled to do so at that time. Everything that I saw and felt in that political and social atmosphere was naturally incorporated into my paintings, and that had a lot to do with the intensity of my understanding of society at that time. [8]

Born in 1960, Yue Minjun’s education prevented him from breaking with the complex political associations of Tiananmen. Referring later to his own works, he explained: ‘Tiananmen was a symbol of China’s political economy and everything associated with it, and not only me but everyone wanted to establish a relationship with that space. Even peasants living in remote mountain areas felt that they wanted to get in touch with that locus ’, and finally, Tiananmen ‘became a symbol of the Chinese person’. [9]

Like Liu Xiaodong, Fang Lijun and Wang Guangyi, Yue also had to narrate questions of reality by making concessions and adopting indirectness. In other words, he maintained an attitude of avoidance and distance to express his own views and emotions. In 1991, the critic Li Xianting had already developed the concept of ‘Cynical Realism’ to describe how Fang Lijun, Liu Wei and other artists revealed their emotions to express the new reality. Yue Minjun falls into same category and in the early 1990s, Yue Minjun’s art and was part of a trend of’ cynicism’ together with many other artists. Yue Minjun had a basic political background similar to that of Fang Lijun; both confronted the conflict and contradiction between the stability of the old political system and ideology and the new social reality and concepts, and both had to make difficult decisions about reality as a result:

After I graduated from middle school and went to work, the work unit was at that time still a closed up world, and people seemed to be engaged in constant scheming against each other, leader against leader, leaders and workers scheming against each other, and worker pitted against worker. All interrelationships seemed fragile and very strange. I began to question human relationships that were so different from what I had imagined when I was a student. After I went to college in 1985, I was still idealistic and the idea of serving the country and making some contribution encouraged me to study. Later because of the changes throughout society, these ideas all began to feel hollow. 1989, the year I graduated from college, ushered in the June Fourth events in Tiananmen, and there was an ensuing sense of loss and a loss of any idealism. Perhaps those ideals had never existed and had only hoodwinked people for decades but the social mood was now one of malcontent. [10]

His disillusion echoed Fang Lijun’s observation that ‘the bastard can be duped a hundred times but still falls for the same old trick’, but the question was how to express the absurd reality and psychological condition that had emerged. After using images of friends in his paintings, Yue decided to limit the images to ‘himself’. From the social psychoanalysis of Yue Minjun himself, we discover the basic starting point for his choice of self-image as his subject:

If I wanted to display the absurdity of this society, I had the simple idea at the time that it was better to use images of myself rather than of others. I didn’t saying that I was a fool or the most stupid person! I had that right! The minimum requirement was that it wasn’t a choice I made but something forced on me. This also avoided some of the pressure at that time and might have had something to do with my psychology. [11]

At the same time, Fang Lijun was depicting his own ‘shaved head’, while Liu Wei was painting himself with his army parents. Cynicism dictated the adoption of a mode of self-mocking humor to demonstrate that individuals had been reduced to a state of powerlessness. Indeed, when he was having a difficult day selling water-melon and pancakes, a smile helped the artist cope. Yue Minjun repeats his stereotyped image of smiling in all his paintings, revealing the spiritual stagnation he felt as a result of his bewilderment. As the artist said: ‘Smiling is a way of refusing to think deeply, and when you’re troubled by things and can’t bring yourself to think about them, then that’s one way of getting rid of the thoughts’. [12] To some extent, Yue records his awkward state of mind in his paintings of that period: He had no status, rights or prospects, and he could only attempt to obtain psychological comfort by repeatedly smiling and making jokes. Later Yue Minjun linked his self-mockery with the ancient Chinese philosophy of life:

Perhaps this kind of smiles includes many meanings, including self-mockery, irony and escape in the face of reality. For example, if a question is answered with a smile, then this a kind of philosophy of life. It may have evolved together with China's traditional culture, for example Laozi’s attempt to escape reality and objection to society’s attempts to shackle the natural person, and of course it also has a passive connotation. [13]

In his methods of expression, Yue Minjun employed ‘repetition’ and there was a basis for this in aesthetics. But political reality also used repetition to erase memories. His early paintings show repeated scenes of Tiananmen and the school playground, as well as particular neat gestures. Transformed into a formal language through the artist’s subconscious, the strength of reality (including historical reality) was transformed into the strength of art, semiotically enabling people to explanation things in multiple ways. In most of his works completed in 1993, the content and mood are close to the attitude and position acknowledged by the artist, but compared with earlier works, his style is more distinctive: Lucid and succinct colors, as well as stereotypical and uniform heads that have become the images and symbols of historical and political reality.

Li Xianting characterized these works as follows:

Nearly all sensitive artists face shared existential problems, the reality of survival being something entrusted by various cultural and value modes of the past. After their loss, the strong system of significance that governed their living environment did not change as a result of this loss. But in confronting these difficulties, there was a fundamental difference between this ‘scoundrel’ or ‘ruffian’ (popi) generation and the two earlier generations of artists. The young ‘scoundrels’ did not believe in the dominant meaning system nor did they believe in the illusion of a formal opposition constructing a new meaning. And so they had no recourse but to confront the situation more substantially and honestly. When it came to salvation, they could only save themselves, and their sense of boredom was the most effective method of ridding themselves of the shackles of meaning. Moreover, as reality could not provide them with a new spiritual background, meaningless meaning became their mode of survival and the new meaning of art, being the best path for self-salvation. [14]

As the spiritual state of the generation of new artists came under critical scrutiny, Yue Minjun was no exception. Although artists and critics had already denied the aggressive function of art, as had the modernists in the 1980s, critics were well aware that here Li Xianting was seeing the mood of helplessness expressed by the artists as contradictory and Yue Minjun later said that this was emotionally implicit in his work. Overseas critics possibly did not see the issue in this way. Most of the issues faced by the majority of those who left China in 1989 were very different from those faced by domestic artists and critics after 1989. In 1993, when Chinese artists participated in the Venice Biennale for the first time, Hou Hanru in France wrote as follows:

Why is it that after more than ten years of development, Chinese contemporary art, which has produced such internationally high quality and meaningful work, now sends its first batch of artists to the Venice Biennale, and most (but not all) of the artists paint in the ‘official’ academic style using skilful techniques and concepts to depict the individual’s situation in Chinese society by giving expression to narrow private desires and illusory ‘cynicism’? At least, one of the main reasons is that these young painters who depict Chinese social reality in such a simple and vulgar way have no ideals, and have been rendered weak and feeble by a hypothetical official ideology and so find excuses to console themselves with cynicism. …Yet this was something that those Westerners still controlled by the old cold war period ideology and who expressed an ‘interest’ in China could imagine, understand and sympathize with, taking pleasure in others’ misfortunes. The decision by Achille Bonito Oliva to display these Chinese artists was not based on any depth of understanding of artistic concepts but he was taking this opportunity to tell Westerners that I have been to China and my sphere of influence now extends to that country. So we must ask, is there genuine peaceful coexistence? [15]

Hou Hanru was not lashing out at only Cynical Art, but he quite clearly did not approve of it. He was making a judgment on the context of artistic phenomena, related to art’s ‘ontology’ (art’s conceptual depths), but he was also highly suspicious of teasing works with realist methodology. This suspicion was usually couched in post-modern terminology such as ‘the China card’, ‘post-colonialism’, ‘Western hegemony’ or ‘cultural imperialism’, but artists would see their predicament as dictated by real life. In fact, in a country where artistic phenomena had not been thoroughly transformed by the old political system, it is problematic to what extent the artistic noumenon was even an effective theoretical concept and position. The truth was that reality had already changed, as Cynical Realism and Political Pop demonstrated. If the artists could truly present their personal psychological condition, they would not need to fall into the trap of abstraction or conceptualism, but the linguistic context did not exist. Escape from a doomed reality facilitated the production of Cynical Realism and Political Pop, as well as Gaudy Art and cross-media performance art. Because the ground was prepared by modernism in the 1980s, artists had completely hurdled over the boundary of essentialism, and Cynical Realism and Political Pop had bid final farewell to modernism. After 1995, younger artists no longer worried about outmoded restrictions; they photographed, made installations, did performance art and video, exhibited their work and extended the possibilities of artistic language.

In 1994, Yue Minjun took part in a number of exhibitions: a solo show at Hanart in Hong Kong; 8+8 Chinese and Russian Avant-Garde Art, Schoeni Gallery, Hong Kong; 94 International New Art Expo, Convention Center, Hong Kong; and, Faces behind the Bamboo Curtain: Yue Minjun and Yang Shaobin Exhibition, Schoeni Gallery, Hong Kong. Yue’s art made a deep impression, and people gradually became accustomed to his symbols. In that year, Yue Minjun also began to give greater thought to how he could progress in a more meaningful way. He began to produce parodies of famous Western classical paintings, and moved beyond concepts about everyday feelings. He revised Eugène Delacroix’s Massacre of Chios, breaking away from the basic context of the story and the original starting point of the French artist. For the Chinese artist it was not the historical analysis of the massacre that mattered but rather the concept of ‘massacre’ itself. Why massacre and not peace? Yue Minjun re-designed the work, and added symbols of peace to its background, so that the massacre took on an absurdity. The motive for revising the work was a response to its excessively direct reality; the symbolic meaning of Tiananmen determined that it became standardized by artists as an ideological position when they depicted this site. When looking at a reproduction of Edouard Manet’s The Execution of Emperor Maximilian, he superficially considered the work’s conception and then used his subconscious as an aid to the memory of the event in the painting:

Maybe it was at its inception more concrete and the atmosphere of living in politics was somewhat more obvious. Later I did not find it so enjoyable, so I revised some of the world’s famous paintings. I think people very familiar with the history of art would have had other thoughts and feelings. When I first revised Manet’s The Execution, it was a scene in which a group of revolutionists were going before the firing squad, and as I revised it the composition did not change but I put smiles on the faces of the people about to be executed, and they had laughing, foolish grins. I have a special understanding and feel for this word revolution, and I still think it has special meaning in China. So I painted several similar things at the time, which represented my personal understanding and ideas. [16]

Similarly, the starting point of Yue Minjun’s experiment connected with reality, as he admitted later: ‘When I began painting my revisions of famous works, I wanted to make the characters in the paintings people with whom I was familiar, but I felt that the paintings were too complicated. Later I thought of June Fourth and these democratic fighters looked a little silly. They had no theory and direction, and they just seemed to be venting their feelings, so I painted Freedom Leads the People (Ziyou lingdao renmin)’. [17] The fashion for revising famous paintings began in the 1980s with Huang Yongbing’s Jules Bastien-Lepage’s Haystack Exhibited in Shanghai (Lepare de doucao zai Shanghai zhanchu) and Wang Guangyi’s The Return of Monumental Tragic Love (Ba bei’ai de fugui). Yue Minjun’s revisions differed from those of the 1980s in that his had no guidance from thought and theory. Wang Guangyi had revised works by Da Vinci and Rembrandt and these were based on a metaphysical starting point. In the 1980s when Western philosophy was extremely popular, this New Wave artist wanted to exemplify the point that ‘any attempt at originality is futile’. Within a field already opened up by modernism, experience and interest could provide the structuring for Yue Minjun’s art. In fact, Yue Minjun transposed the images of his own icons to famous paintings, subverting the inherent cultural logic of the original work in linguistic subject and interest, just like Western commodities that are altered when they enter the Chinese market, to conform to the new linguistic context. In the process of deconstruction that accompanies cultural interaction, Yue Minjun’s successful ‘revisions’ were subversive aesthetic products that enabled people to understand and accept the interesting meanings of the works, in keeping with contemporary art’s typicality. In Freedom Entices the People (Ziyou yindao renmin, 1996) Yue Minjun radically revises Delacroix’s famous work La Liberté guidant le people and places the event in a contemporary Chinese environment. Skyscrapers can be seen in the distance and the buildings symbolize the characteristics of the times in which the artist lives. Under blue sky and white clouds, a group of Yue Minjun icon figures are the ‘warriors’ leading the Goddess of Freedom, the mock version of the Statue of Liberty brought into Tiananmen by art students in May-June 1989. But the warriors seem aimless, as though performing in a boring play, and the warriors playing dead on the ground are getting a belly laugh from the other characters. The painting hints that the Goddess of Freedom is being guided by the actors (or the Yue Minjun look-alikes) from Tiananmen to the Sanlitun area. The artist has substituted the call of the Goddess of Freedom but there is none of the cruelty of revolution or the loftiness of romanticism in the work. What people see is only a Chinese farce, and the artist has only crossed the bridge represented by this famous Western painting, so that more people can understand the reality, taste, boredom and pessimism that he expresses. Here, the art history principle is secondary and, unlike Wang Guangyi whose real starting point is cultural revision, Yue Minjun’s approach to the context for his works is best described by the artist:

I think a lot of ideas were proposed at that time by people with an idealist complex, who didn’t think conscientiously and a lot of other human elements were also mixed in. Many of the ideas were very funny; maybe they were suitable for teaching beginners. But maybe other ideas were a mess. Many things in China are not very mature, but they come out directly and often make things complex. [18]

This starting point naturally encompassed unconscious introspection on the ‘emancipation of thought’ that took place in the 1980s. In the mid-1990s, Yue Minjun overcame his earlier poverty and he began to think about artistic questions in a calmer way. Of course, in the series of revisionist works, the artist was clearly playful and relaxed, having virtually abandoned his modernist dualism and he was beginning to engage with the business side of being an artist. He had moved on in producing his Yue Minjun lookalike faces, and as in cartoon production, was beginning to place these unchanging and non-aging icons in any place, any era or any linguistic context:

I began to use that image consciously and constantly. I was hoping that I could use it like in a cartoon picture, not as an external image, but as the meaning of the central cartoon character. I could live on but the cartoon image would remain ageless, and in the same way in which I placed it in La Liberté guidant le people I could insert it in any historical story where it could play a role. He could live on and have a reason to live on. [19]

His observation of commercial society was also reflected in his Make-up series (Huazhuang xilie) which he began in 1995.

The living environment at the Yuanmingyuan artists’ village became complicated as the number of artists moving there increased. Political forces and other factors led the artists to progressively disband around 1995. Prior to then, but also in 1995, Yue Minjun and Fang Lijun had moved to Songzhuang, where they set up a new working environment. [20] In 1998 Yue Minjun began working on his Locations series (Changjing xilie), in which he removed the figures from famous paintings: Dong Xiwen’s The Founding Ceremony of the Nation (Kaiguo dadian), The Capture of Luding Bridge (Feiduo Ludingqiao), Jacques-Louis David’s Leonidas at Thermopylae, Claude Monet’s Déjeuner sur l’Herbe, and Johannes Vermeer’s The Lace-maker. If we read these works out of context, people can only comment on the artistic interest of different works. However, different audiences can read different meanings into the works because of their own background knowledge. How do audiences familiar with China’s history, for example, read the meaning of Dong Xiwen’s The Founding Ceremony of the Nation and The Capture of Luding Bridge? Yue Minjun said that from 1997 on he began to completely give up scenes of opposition and conflict, but those who understand China’s history asked why works that were highly praised, such as The Founding Ceremony of the Nation and The Capture of Luding Bridge, were now limited to being artistic questions. The artist has discussed the starting point of this experiment:

My earliest idea was that an artist should always fill in things and add things. I had never subtracted elements, but unless the canvas was reduced there was no way to present my concept, so I had to think of things with which everybody is familiar, while removing a part, to create a feeling of subtraction, and providing a contrast, so that people would ask where all the people went. [21]

However, ‘things with which everybody is familiar’ are things of history, and they provide the basic context in which people know and understand society and reality, and in reading such works they will add things constantly. By ‘subtracting’, the artist effectively ‘adds’, and provides a new perspective for reading the same work. So, one possibility is a purely artistic concept, while still being unable to flee from the context of society and history.

The Founding Ceremony of the Nation (1998) was a revision of Dong Xiwen’s work of the same title painted in 1953, and it records a major event in the history of the Communist Party of China. In this depiction of Mao Zedong proclaiming the establishment of the People’s Republic of China the artist wanted to create a ‘magnificent’ effect, in which this awesome scene occurs on a day of gentle breezes and warm sunshine. However, because of the Communist Party of China’s internal political struggles, the line-up of personages who appeared on the gate tower of Tiananmen was revised several times. In December 1954, the Central Committee took the decision to eliminate the North-eastern leaders Gao Gang and Rao Shushi, and in accordance with the Party’s demands, the artist eliminated those persons from the work. After the outbreak of the Cultural Revolution, Liu Shaoqi was regarded as a ‘traitor’, even though he was second in status to Mao, and his image was replaced with that of Dong Biwu. Later, there were calls for the elimination from the work of the image of Lin Boqu, a highly qualified member of the Communist Party of China Political Bureau, who had objected to Mao Zedong marrying Jiang Qing. However, the artist Dong Xiwen had been diagnosed with cancer in 1971 and was unable to carry out the alteration. His revisionist modifications were inherited by Jin Shangyi, who later simply repainted the work. To comply with political requirements, Jin Shangyi kept changing the faces again and again, and after the conclusion of the Cultural Revolution, Liu Shaoqi’s image was dramatically restored to the painting. Against such a historical background, Yue Minjun’s ‘subtraction’ might constitute a political attitude, and it did raise a question: Where on earth did the great men of history go? In ancient Chinese literature there many stories about ‘abandoned rooms’, but these are usually allusions to the love of wives for absent husbands. But the meaning of this serious historical juncture was distorted and the resulting work The Empty Building (Renqu loukong) had the effect of highlighting the political question.

In 1999, Yue Minjun accepted Hick and Sherman’s invitation to the Venice Biennale and this exhibition again highlighted the importance of ‘repetition’ in Yue’s work and he noted that ‘many of my works highly depend on repetition and they can visually extend the space occupied in a way that an isolated work cannot because it lacks the strength’. [22] Thus, he decided to not only use repetition in paintings, but to use it for visual effect in three-dimensional space, and so began to make sculptures:

After I returned, I wanted to make the idiotic figures which I had painted in the past more interesting, and so I thought of making sculptures. I quickly began making my version of terracotta warriors and I was churning them out. I remember reading in a book that no two of Qin Shihuang’s terracotta warriors have the same expression; all were the same and formed an oppressive throng. Believing that there had originally been more than 1,000 clay figures of warriors and horses, my idea was to begin by making that many. My first batch was to consist of 100 figures, but after turning out 25, I realized that there would be far too many, and so I contented myself with making the group of 25. There would be nowhere to store an army of more than 1,000. If I had the space, I imagine that this repetition would have been extremely impressive. [23]

When he was making The Modern Entombed Warriors #1(Xiandai bingmayong-1 现代兵马俑—1) and The Modern Entombed Warriors #1 (Xiandai bingmayong-2 现代兵马俑—2), he also embarked on print-making that was ideally suited to his propensity for ‘repetition’.

In 2003, during the SARS epidemic, Yue remained at home as much as possible and worked on his sculptural project called the Romanticism + Realism Research series (Langman zhuyi + xianshizhuyi yanjiu xilie). The artist again inserted the language of mockery into a serious historical issue.

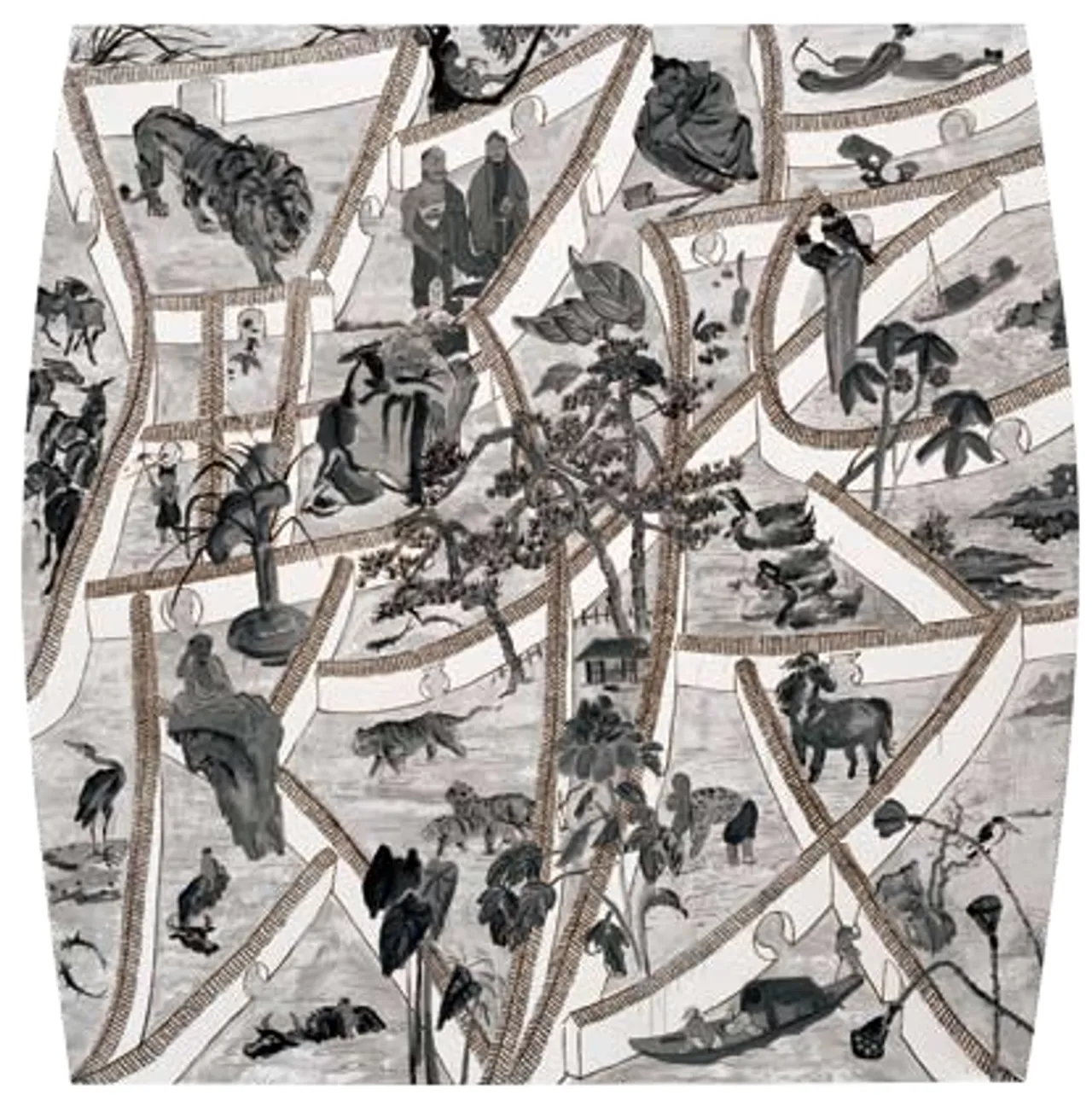

In 2004, he completed his Wild Crane in the Drifting Clouds series (Xianyun yehe xilie), from which all social and historical elements were expunged, enabling people to clearly see characteristic Chinese motives of gamesmanship.

In 2006, Yue Minjun showed his work titled Looking for Terrorists (Xunzhao kongbu fenzi) in the Maze series (Migong xilie) at his exhibition of the Looking For series (Xunzhao xilie) at the Beijing Commune gallery in the 798 art district in Beijing. In a children’s playing space, the seriousness and validity of the Looking For series were highly doubtful. The works revealed that the artist was attempting to pictorially adjust and change his art, by broadening their mental range and perspective. Terrorism is an important globalized concept, but as a concept it is also suspect. The question emerged: What and how were we looking for, as the titles of the works suggested we do. The questions were hypothetical, and in a world of games in which cultural and historical reasons do not determine the rules, any starting point for genuine issues was relative and unreliable.

Leng Lin wrote for the following for the exhibition:

Terrorism has already become one of the most important, most serious and most urgent topics discussed in this era. But during this exhibition when we look for the terrorist, Yue Minjun seems to be calmly asking: What are we looking for? Are we looking for something that we ourselves created? Is our blood flowing with patriotic fervor sprinkled on a single-handle cup? In this era, the art of the entire world has been already exhausted in pluralistic cultural structures, and it seems that the search for enthusiasm that fired the modernist age is with us again. The artist Yue Minjun uses the search to oppose the search, and he uses the urgent topic of terrorism to enter a sphere of debate. He uses colors and images from Chinese traditional folk art to construct his views of terrorism, and in this scene, the happy and joyful impression of a specific terrorism seems funny. (2006)

Yue Minjun is a thinking artist, although he appears silent and rarely given to words. Throughout his artistic journey he has maintained a reading and an analysis of issues. Perhaps, from the very beginning, Yue Minjun’s work was only an instinctive resistance to his individuality and an unconscious acknowledgement of his own existence, and a call to arms and a scream of rage issued to a society that totally disregarded his self. However, when his art become the focus of social attention and he was financially rewarded, the artist found it difficult to extricate himself from the responsibility of thinking seriously about concepts like art, society, mankind and values.

The complexity of reality and the information bombarding him from all directions require him to reflect in whatever fragmentary, incomplete and ever-changing way. He ponders the relationship between the individual and society, but he believes individuality is only approved by society when everything is fully explained, prior to which people totally ignore the individual who has no authority. He reminds us of the importance of ‘face’, and more mundanely makes us aware of the importance of having a presence in society, ‘television having the power to make you more important. If you want to have a famous face, you should have some outstanding characteristic’. He even believes that this society forces every individual to strive to state and express their values, so that people can see a brand-new individual character. In this way we can easily call on the succinctness of classical modern philosophy, for example:

Without me, there is nothing; without the individual me, everything has no meaning; I am aware of myself because I exist; I exist, so I can feel everything; in fact we respect people because the people we respect are always aware of their own existence. Everyone wants to become a celebrity, and those who are celebrities all have their own methods. My method is painting myself, and for the present time at least I want to go on painting myself. ‘One must never forget oneself’.

In the past, the philosopher told people: ‘I think, therefore I am’. Yet Yue Minjun wants to say: A statement by an individual is more effective than metaphysical thinking, even if you only reveal that you are alive. In this way, the range of art is not what is described as ‘beauty’:

Art is sometimes a way of looking at beauty, a way of looking at politics or a way of looking at science. It is a way of observing, thinking and behaving. In the past we tried to express ourselves and think; now I feel that it is a way of looking at things, a more important way of looking at things than in the past, but forms are not important for art. Pay close attention, and art will transform into a way to view particular things. The study of vision is also not the most important thing, because if you only look at things visually, you can become ignorant.

Since the question of thought is so extensive and art has been involved in all questions of civilization, Yue Minjun, as an artist, would not seem to have limited his visual range at all. He is concerned about questions of nationalism, region, language and customs. He is concerned about global issues like migration and urbanization. He is concerned with religion and the results of scientific and technological changes. He is concerned about communications and the lack of mutual understanding between people in new environments. He has even speculated as follows: ‘There are distances between people who do different jobs. Computer people basically cannot till the soil, biologists basically do not know anything about physics, and people who smoke marijuana do not know that there are any other pleasures. Perhaps the world could conform to the different pleasures; different cultural characteristics and different lifestyles of different people, and the whole world could be divided up into marijuana people, computer people, fishing people and painting people. Only when all these circles of people mix together can people have their own fun and their own cultures. Perhaps future conflicts will occur between people with different hobbies, with conflicts between smokers and non-smokers, or between computer people and non-computer people’. However, any question relates to one’s own existence, because the self is the one concrete life a person can experience, and the function of art is to display the self. When he was young, he was inspired by Shen Congwen’s characters, and he thought that being close to life was a correct rationale, regardless of whether or not this rationale has firm theoretical foundations. He insists on this rationality and describes his work as ‘staying close to one’s self’. Because he cares for himself, he ponders social, historical and other problems related to his self, and we can see that his relationship with the world is a complex contemporary casebook.

Naturally, what people remember most is Yue Minjun’s ‘beaming face’ and that is what he is concerned with and what he expresses. Even though this smiling face is part of a life in the past and present, East and West, city and village, his face in real and historical images has become a symbol of the spirit of this age. Few artists have created such an icon, but that icon now represents Yue Minjun’s intelligence and talent.

Wednesday, 12 March 2008

NOTES:

[1] Taken from the first of Yin Jinan’s lectures at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, May 2005.

[2] Idem.

[3] Idem.

[4] Idem.

[5] Liu Chun, ‘Artworks Should Represent the Artist’s Attitude and Stance: Interview with Yue Minjun’ (Zuopin yinggai daibiao yishujia de taidu he lichang: Yue Minjun fangtan lu), 2004.

[6] Taken from the first of Yin Jinan’s lectures at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, May 2005.

[7] The Last Romantics: Record of the Lives of Beijing’s Free Artists (Zuihou de langman: Beijing ziyou yishujia shenghuo shilu), Beifang Wenyi Chubanshe, 1999.

[8] Leng Lin, “Proceeding from the Self: Interview with Yue Minjun’ (Cong ziji chufa: Yue Minjun fangtan), 1999.

[9] Taken from the first of Yin Jinan’s lectures at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, May 2005.

[10] Li Xianting, ‘The Making of a Superficial Idol: Discussion and Criticism of Yue Minjun’s Work’ (Fuqian ouxiang de zhizao: Guanyu Yue Minjun zuopin de duitan he dianping), 2002.

[11] Yang Wei, ‘Physical Escape and the Search for Consciousness’ (Shenti de taoli yu yishi de xunzhao), 2006.

[12] Liu Chun, ‘Artworks Should Represent the Artist’s Attitude and Stance: Interview with Yue Minjun’ (Zuopin yinggai daibiao yishujia de taidu he lichang: Yue Minjun fangtan lu), 2004.

[13] Jiang Jiehong, ‘Interview with Yue Minjun’ (Yue Minjun fangtan), 2006.

[14] Li Xianting, ‘The Sense of Ennui and the Third Generation of Post-Cultural Revolution Artists’ (Wuliaogan he ‘Wenge’ hou de disandai yishujia), August, 1991.

[15] ‘The Myth and Reality of the 45th Venice Biennale’ (Di 45 jie Weinisi Shuangnianzhan de shenhua yu xianshi), Xiongshi meishu, Taipei, no. 2, 1993.

[16] Liu Chun, ‘Artworks Should Represent the Artist’s Attitude and Stance: Interview with Yue Minjun’ (Zuopin yinggai daibiao yishujia de taidu he lichang: Yue Minjun fangtan lu), 2004.

[17] Li Xianting, ‘The Making of a Superficial Idol: Discussion and Criticism of Yue Minjun’s Work’ (Fuqian ouxiang de zhizao: Guanyu Yue Minjun zuopin de duitan he dianping), 2002.

[18] Taken from the first of Yin Jinan’s lectures at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, May 2005.

[19] Yang Wei, ‘Physical Escape and the Search for Consciousness’ (Shenti de taoli yu yishi de xunzhao), 2006.

[20] Liu Chun, ‘Artworks Should Represent the Artist’s Attitude and Stance: Interview with Yue Minjun’ (Zuopin yinggai daibiao yishujia de taidu he lichang: Yue Minjun fangtan lu), 2004.

[21] Li Xianting, ‘The Making of a Superficial Idol: Discussion and Criticism of Yue Minjun’s Work’ (Fuqian ouxiang de zhizao: Guanyu Yue Minjun zuopin de duitan he dianping), 2002.

[22] Idem.

[23] Idem.

Translated by Dr. Bruce Gordon Doar