Zeng Hao: Daily Life as a Micro-History

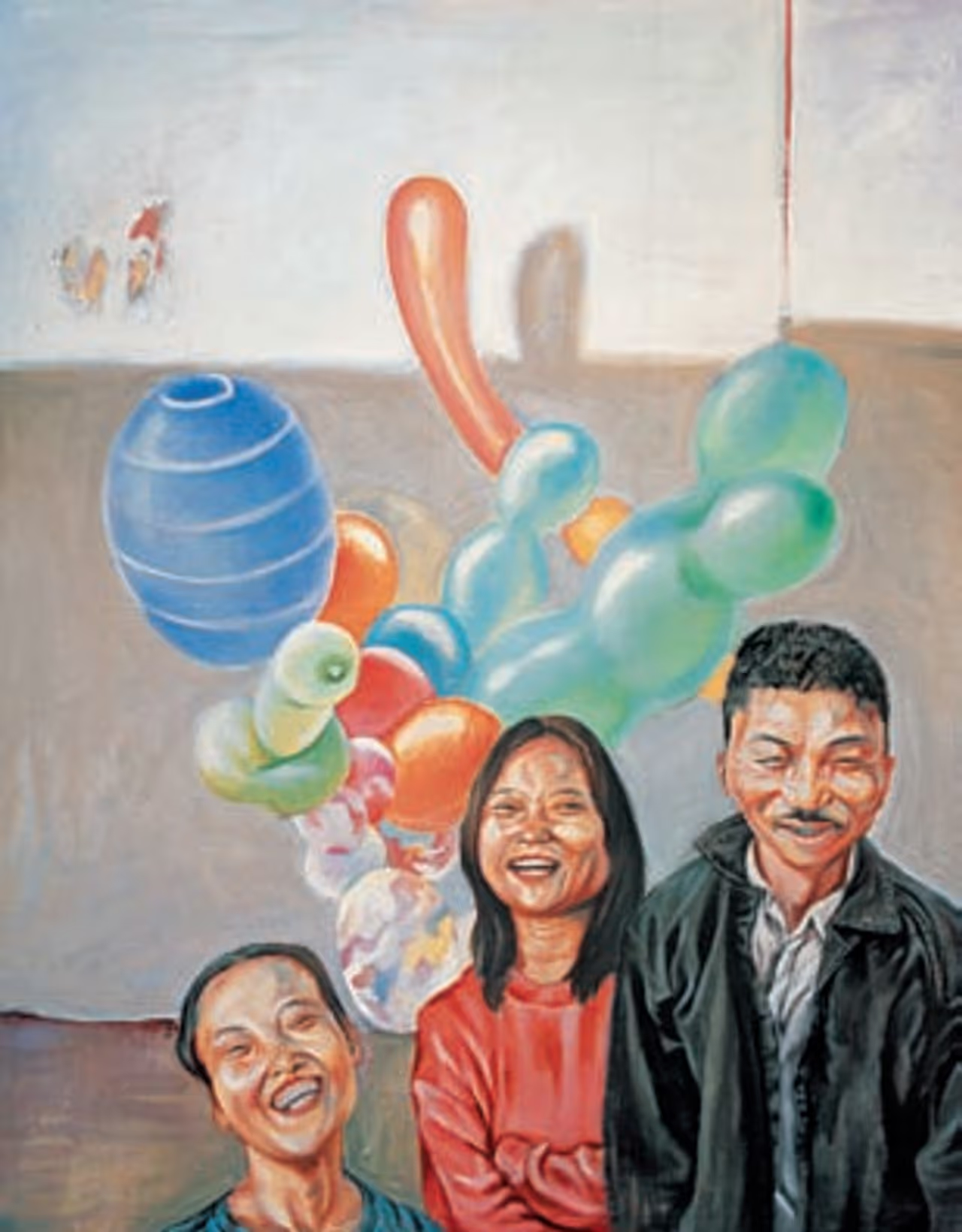

In 1992, at a Guangzhou army hostel fourteen critics had gathered to evaluate paintings from all over China for the upcoming Guangzhou Biennale. Among them, they saw works that had been roughly finished; many had meticulous brush strokes, but the colors were not carefully balanced and they appeared superficial; and those with images of bored men and women could even be described as ‘unbearably ugly’. The exaggerated smiling faces of young people with balloons floating behind them looked out at their audience, but the critics could not determine why on earth the faces were smiling so foolishly and why with such boredom. The critic Yi Ying promptly characterized these works as ‘bad paintings’ (huaihua). Zeng Hao’s works were not put into any of the award categories, although some critics already noted the particularity of his work, but failed to notice that his paintings were part of a general trend, the spiritual content of which was that there are no factual things that are meaningful, there is no philosophy that has value and the meaning of this world itself is even highly suspect. Unlike the tragic mood that typified some earlier modernist works, this new art demonstrated that even tragedy itself had no meaning. Gradually, people in the cultural and art worlds discovered that what someone described as the ‘post-modern’ period had arrived, except that the use of this Western term to describe this new artistic phenomenon was over-complex and excessively vague. In 1991 in Beijing, Liu Xiaodong had already completed a large batch of New Generation works, but prior to this his Herdsman Pastoral (Tianyuan muge, 1989) had already demonstrated mastery of the academically taught skills and techniques and had transcended the academic style to stand out as a work of great emotional range. The paintings displayed at the New Generation Exhibition in July 1991 had been described by the critic Yin Jinan as works with ‘close-up range’ (jinjuli), a term referring to the exclusive treatment by the artists of only what was in their direct scan of vision to the exclusion of all else within range. In 1992, there had been an exhibition of works by Liu Wei and Fang Lijun at the Beijing Art Museum, and prior to this work by Fang Lijun and Liu Wei had been described as Cynical Realism by the critic Li Xianting, after an earlier exhibition not open to the public. Regardless of the differences in the two painters’ styles, their characters all demonstrated the same helplessness and defeat, demonstrating a resolute effort to resist any aesthetic construction. Certainly, before 1992, there had been a lengthy oppressive period in the wake of the events of 1989, which had begun in April with the commemorative activities for Hu Yaobang in Tiananmen Square and ended in June with the final ‘clean-up’ of the square. This was followed by a stunned period, in which ‘the magpies blankly stared’; the whole of society was under tight control, as people went about satisfying basic needs and ensuring their personal security. From 1989 to 1992, there were very few modernist art exhibitions anywhere in China, and so everyone was curious to see what sort of work would be presented by artists for inclusion in such an extensive exhibition as the Guangzhou Biennale.

Zeng Hao lived through the turmoil of 1989. Born in 1963, he had graduated from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in 1989 but, because of the political upheaval euphemistically termed ‘the June 4th events’, he and his classmates had been unable to stage the usual graduation exhibition. In the midst of the political confusion he drifted from Beijing to Wuhan, and then on to Chongqing. China was still what was called ‘a planned economy’ and a vagrant person without a job was deemed to be someone without value. And so, not serving as a cog in the machinery of society, Zeng Hao drifted for a year:

It was more difficult to find a job at that time and during the year after my graduation I travelled around Sichuan and Guangdong looking for a job. I hadn’t set my heart on anything in particular and was playing around in a way. I wasn’t very conscientious and would often give up on things halfway. I’d run away after making contacts and so after a year of this I still hadn’t found a job. I ended up going back to Yunnan and got a job as a teacher in the Kunming Education Institute, where I was in charge of middle school art education.

For Zeng Hao, the work in Kunming was steady and secure, and his life and work changed. Although he began to realize gradually that he would have to rely on his own efforts in the future, Zeng Hao was not yet sure what sort of future he wanted. He had immediate identity issues, as well as future concerns, and needed to address them.

In his early years, Zeng Hao was more or less forced into studying art. As he remembers, his father who was a chemist had always wanted to be an artist and thought his son should study art, but Zeng Hao was not sure what that entailed and what his childhood memories had to do with art. He remembers how in the Cultural Revolution years his teachers were criticized and denounced, antiques and books were burnt, and his parents were transferred to the countryside. He wondered whether, even if could have painted from life in the countryside under the tutorship of his father, this would have satisfied his inner needs. To a great extent, for Zeng Hao, studying painting was little different from mandatory labor forced in him by his father, and he looked back on his early study of painting as lacking any passion or impulse. Beginning studies in 1979 at the middle school attached to the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts was a fulfillment of his father’s own artistic complex, but it was also an opportunity for Zeng Hao to escape from his father’s control. The important thing for him was not having the opportunity and environment in which to study painting but having the possibility of freedom from his parents’ control. At the school Zeng Hao demonstrated no particular aptitude or artistic talent and felt ‘especially happy’ because there was no strict control, he could cut classes and avoid homework. He was fond of making mischief, like cutting the power supply to the school, and became so unpopular among the teachers that they felt he needed to be punished. Because of his undisciplined behavior, he was eventually excluded from admission to the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts. For the teachers, he was a ‘bad student’, just as he had been a bad child’ in his father’s eyes. After returning to Kunming, Zeng Hao felt increasingly at a loss and troubled:

The people around me are all doing things that have a sense of belonging, but I seem to be at a loss. I feel that I have been on a train that just kept on going, where I’ll never know, and got dumped at a platform along the way. So I decided to be serious about I do in the future and given it a lot of thought. Painting suits me, so I should start treating it conscientiously. A genuine interest in art will only come with step by step training.[1]

Among the art instructors in Kunming, Zeng Hao got to know Zhang Xiaogang and Mao Xuhui, with whom he discussed questions related to art and life. These two teachers were at that time quite depressed, and in their reading of Western philosophy and literature, they were beginning to re-assess life. They were fond of music and, when they were drinking and chatting, Western music would be playing in the background; they felt they could appreciate the state of mind and mood of modernist artists, in that atmosphere in which Western sensibilities were taking hold among young Chinese. After the end of the Cultural Revolution, the critical stance of Western modernism was something young Chinese sought to emulate. However consciously and unconsciously, things carried on, and even if a melody of Rachmaninoff did suddenly bring about a change in attitude or even worldview in a listener, this was only probably because this was a period in which there was no approved worldview, except for the Western spirit that encouraged individual strength and skepticism. In this way, Zeng Hao unconsciously took on a set of values that were quite different from those of his father’s generation. Individuality and independence imperceptibly became goals that would determine his future. At this time, painting increasingly interested him to the point where, although he had not yet decided to make it his future career, he began to consider it as a pleasure and an option like working, drinking and sleeping.

For Zeng Hao, schools and their discipline symbolized control and so when he received the admission brochure from the Central Academy of Fine Arts he was not wildly excited about the prospect of resuming his study of art. He reasoned that Van Gogh and Cezanne had never had formal training:

Zhang Xiaogang later urged me to sit for the exams, and so I regarded it as a stage in growing up. He told me that after I was admitted, if I didn’t want to study then I needn’t go and later I could look on it as a choice I’d made. But if I didn’t sit for the exams, and later thought about turning down the opportunity, I might regret it forever.[2]

Zeng Hao was surprised when he was admitted to the Central Academy of Fine Arts, and had to again submit to the discipline of school, but his new circle of friends loved painting and he too began to experience the pleasure of having his own talent recognized. During his four years at the college he was subjected to its strict discipline but was instinctively unable to accept any of the well-worn dogmas that were imparted. However, when a teacher challenged him to explain his own ideas on art, he was at a loss.

The four years he spent at the Central Academy of Fine Arts were vital years in the history of contemporary Chinese art. This was the period of the ’85 art movement and, obviously, teachers and students at the college were constantly being bombarded with new information about art; there was a dynamic atmosphere in which ideas met with skepticism, judgment, critique, disputation and acceptance. For Zeng Hao, the important thing was not his art training; he genuinely began to think about art and understand it. It was when Zeng Hao finally travelled back to Kunming, determined to grab the opportunity to go into business and make money, a craze sweeping China at that time, that he suddenly realized that art appealed to him far more than being envied for his business acumen:

This was when I first realized that I seriously wanted to go on painting … I had studied art for a total of eight years (four at the school and four at the academy) so it seemed crazy to now do something I knew nothing about and had no interest in. That’s when I decided to make the decision.[3]

So we find ourselves back at the start of the 1990s, in those days when people had no direction and suffered ennui. The most obvious characteristic of this period was that people no longer discussed questions of ideology; only the enticements and predicaments of commerce exercised people’s wits to the fullest. It was at this time that Zeng Hao went to Guangzhou looking for opportunities. He was asked to work as a substitute teacher at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, but he had not done that sort of work for a long time; he was probably hoping to find other work in Guangzhou, but had not really looked conscientiously into the matter. To a certain extent, Zeng Hao was still quite confused about what he wanted to do, and it was then that he decided to try to enter something in an exhibition. However, his training at the institute and his understanding of art had already gradually changed his own attitude to art, and while his attitude might not be altogether clear it was decidedly individualized. Everything read, heard and experienced forms a personal artistic language that, once it appears on canvas, demonstrates the artist’s uniqueness. While Zeng Hao was surrounded by the objects and symbols of the commodity society, he felt that it was difficult to express the social significance of these sundry, tawdry and boring one-off items. People moving in this material society had no metaphysical ideals or goals and did not believe in the value of spiritual goals. What then was the meaning of life? The ‘consummate skills’ of the professors at the institute were not up to the task of expressing such a world. How could they depict in any detail the world of the alleys where goods like underpants and bras hang from every wall and advertising draped with photographs of scantily clad women proclaimed the quality of different products? Only ‘tacky skills’ could realistically capture this world, and he felt such technical treatment was consistent with the subject matter he wanted to paint. In the 1980s, technique had become suspect, even though modernism retained a degree of interest in classicism, but commercial society which had totally abandoned the quest for essentialism demanded that art undertake a conceptual transformation.

In his works completed in 1992, Zeng Hao’s own image appears, revealing that the life depicted in the paintings was life as Zeng Hao saw and experienced it. Balloon Series #2 (Qiqiu xilie zhi er), which he entered in the 1992 Guangzhou Biennale, depicts an instant in which a man hopping onto a pushbike gawps at a smiling woman in front of him, a response within the ‘close-up range’. In this series, to which balloons lent the title, the images provide the symbolic and metaphorical suggestion that life is glittering and vacant. Yan Shan, a member of the judging panel at the Biennale, prefaced his explanation of the work with a comment on the painting’s content and psychological mood: ‘Through his careless brush work and clumsy modeling, the artist expresses his disdain for dry and dull modern life’. The critic did, however, reveal that he was aware that a new technique documenting a new psychology had appeared: ‘This is representative of many of the exhibited works that conform to an anti-aesthetic of bad painting’.[4] The issue was that artists had rejected the principles of classicism and even the elitism latent in modernism, as well as anything that hinted at relative status, whether it be in content, expression or taste. In fact, Zeng Hao’s bad painting took its place beside many other works entered in the Guangzhou Biennale in which every effort had been made to renounce essentialism, including Zhang Yajie’s Big Glass Window (Da boli chuang), Wang Jinsong’s Another Fine Day (You shi yige da qingtian), and Song Yonghong’s Old Couple (Laonian fuqi). Zeng Hao, however, went further than these other artists by also rejecting any civilized promises regarding expression and technique. As he saw it, these ‘consummate’ technical skills were neither wanted nor needed by his work. In this regard, his ‘bad paintings’ and the works of Beijing’s New Generation and Cyncial Realists had much in common.

Around 1992 Guangzhou was a booming and ebullient business environment. Apart from extending the possibility of money, the colorful reality of Guangzhou did not demonstrate any cultural ‘elevation’; as in Zeng Hao’s paintings, apart from the bras and underpants hung out for sale and the constantly replayed songs from Hong Kong and Taiwan, pedestrians rush by, motorcycles whizz past and the sidewalk snack booths are open all night, but the next day you find yourself lost, without rights and without money. Was this sufficient reason for walking the streets of Guangzhou, and what kind of ideas does this produce in an artist?

Thinking of change is not like plying a trade or being able to come up with something. At that time I wasn’t satisfied with this kind of life so I decided to go to Guangzhou, and in Guangzhou I began to slowly change, experience things and think about things.[5]

During the Guangzhou Biennale, Zeng Hao had already begun to do substitute teaching at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts and began to feel that this was a city with an abundance of sunshine like Kunming. He had more time to look at what he believed to be the real questions. In mid-1993, Zeng Hao decided to accept full teaching duties at the academy. Zeng Hao remained concerned about the question of subjectivity and, in conformity to modernist logic, assumed that people were the subjects in question, but the meaning of the subject remained elusive. In his works of 1993, including Angler (Diaoyuzhe), Ice Popsicle (Bingbang) and Take One More Shot (Hai yao zai pai yizhang), the state of mind of his subjects was not expressed, regardless of their social station. The life content reflected in his works ranged from the mundane to the intensely boring, but that was life as the artist saw and experienced it, and his reality was this sampling. However, it is difficult to assess the artist’s degree of enthusiasm in painting these works, because this articulation of his psychological condition at this time, with the exception of lustful and stimulating incidents, fails to sustain interest, even in the people he is depicting. The humanist position and communal responsibility aroused by artists in the 1980s had totally lost their impact and the system of social judgment had become isolating. How could people call something meaningful? In fact, the reasons why the question of ‘meaning’ was discussed within critical circles in 1993 were illogical. Reality had opened up larger issues and blind spots, and there was no longer any point in determining whether people had lost their capacity for judgment, when the original system for making judgments was no longer effective:

As you slowly grow up, setbacks constantly make you adjust and adapt to society. I began by looking at the relationship between people and things. My earlier paintings contained animated elements and from the images it is clear that people were the center of my work, and I always felt that a painting had to have a theme. But later I thought that when we consider a lot of things, we do not have a clear theme. Everything is fraught with contingency and possibility, and so people and things have slowly begun to run along parallel tracks in my paintings.[6]

This city of Guangzhou provided an environment for examining the direct relationship between people and things, but he discovered that giving up working on ‘themes’ was the most important aspect of transforming his own attitudes. If we place the artist in the context of desire-drenched dullness, we find that the living person and the goods on display on the shelves have much in common. Entering a red light night club, where the man with the mobile leaning on the glass is eyeing off a young lady inside and a ‘crisis of the flesh’ is looming, for other people in that environment any discussion of ‘meaning’ is ridiculous. During his four years living in Guangzhou, Zeng Hao experienced problems of life outside his painting. He began to feel that people were not important, their importance being on the same level as that of objects, and in his works of 1994, he also began to diminish the significance of space, depicting either only tree leaves (Sunday, Xingqitian) or small items of jewelry (Flowers, Huar). However, the artist retained a sense of warmth; his friend Ye Yongqing is depicted in the foreground of one composition as the artist’s vision of a friend, but because he is so well known to the artist, the image is very easy to discern.

Zeng Hao found, however, that his elevation of material objects above people was an irreversible abandonment, and by 1995 he only depicted material items such as the desk in Make-up (Huazhuang), or rejected physical space completely, as in Yesterday (Zuotian). Throughout that year he either emphasized the importance of there being no basis in space or drastically shrank figures as though they were ordinary material objects, the only difference being their shape, and he scattered them about indifferently, like other items such as fans, leather shoes or combs. The works that the artist finished in 1995 presage his future work, and in them people float in space like weightless objects.

Indeed, in the works finished in 1996 we see the full development of this trend. In the works of the previous year, he had still maintained the basic relationships between people and material objects, and when he was consciously concerned with people he positioned them conspicuously, as in 10 August 1995 (1995 nian 8 yue 10 ri) and Sunday Afternoon (Xingqitian xiawu). However, in the works of 1996, people have been shrunk as much as possible, although he considers the relationship between personages and articles for daily use to be more or less proportionate, but Zeng Hao is saying that there is no difference between people and articles. What merits attention is that in the works before 1996, it is very difficult to see hi-tech daily items; there are only antiquated or obsolete knickknacks. Zeng Hao was perhaps thinking fondly of the old days of bustling Canton and he could only find comfort in memories triggered by these mementoes, given his difficult circumstances at that time. However, in 1996, everything that now confronts the artist is powerful and irresistible. He begins by simply depicting TVs, but over time the objects and scenes in his works move up the high-tech ladder.

In the 1990s, cities like Guangzhou and Shenzhen were beginning to acquire dazzling buildings and spaces, and people with money imagined they were living the high life because they had everything, even gold bath taps. These overnight millionaires needed tradesmen to decorate the interiors of their mock foreign palaces and Louis Quatorze furnishings and the like entered the repertoire of Chinese commercial concepts. The Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts where Zeng Hao taught began duplicating Greek sculpture and Roman columns. Teachers became actively involved in commercial city construction projects, churning out replicas of Western art works in materials ranging from inferior gypsum to exquisite marble. But all these Western symbols or façades could not conceal an inner blandness. Curiously, when a person concocts a material myth for a created façade, other people, even those with an education, are somehow in awe of the myth. When he saw how friends were losing the ability to enjoy the objects in their own new homes, Zeng Hao became keenly aware of the authority exercised by designed and manufactured objects that served their owners into servitude. They were no longer objects that people could use as they saw fit:

That experience makes one alarmingly aware of the interesting relationship that exists between people, the environment, space and material objects. People work hard to make their lives more free, casual and comfortable, but eventually find that, for all their diligence, they cannot work out whether the chairs are there to serve them and they are there for the sake of the chairs. People become extremely fastidious. In these situations I feel that the people are just like the chairs; they can be moved around in the same way but not too freely and one has to be very careful. In such living spaces, I’m very interested in the nature of the relationship between the people and the environment. I have always been interested in such relationships, but have never found an accurate means for expressing it, although I find it very enlightening.[7]

He made this observation in 1993, but he had experienced this problem on a daily basis over a long time; he felt powerless within a reality from which he could not extricate himself. He said that he wanted to ‘create a scene of tranquil insight, from which he could experience the relationships between space and people, space and objects, including the relationships between people and objects, as well as between objects themselves’. The method that he adopted was to completely expunge the importance of people from his compositions. However, he paid close attention to the content of life, whether they were home furnishings, e.g., 15 May (5 yue 15 ri), or streetscapes, e.g., 20 September 1996 (1996 nian 9 yue 20 ri). He never completely renounced ‘meticulous’ description, fastidiously depicting items from everyday life such as sofas, chairs, cupboards, lamp-stands and even shoes, and taking care that he showed no connection between them. At the same time, he exercised the same meticulousness in depicting human figures; careful examination reveals that even though their dimensions are the same as his material items, these figures adopt the same poses and seem subject to the same moods as proportionately scaled figures. Like his randomly scattered articles, there is also no interconnection between the human figures, even if we might imagine them occupying the same space, e.g. 10 PM (Wanshang 10 dian).

Interestingly, because his views on reality and his methodologies were so at odds with the leadership of the institute, Zeng Hao’s teaching position at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts was under threat, and while he revised his teaching methods and stopped handing out daily use items such as condoms, deemed by his superiors to be tacky, to students to demonstrate his educational points, his art and his teaching both failed to meet with the approval of his bosses. There were teachers of many different types at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts. Some ran interior decorating companies or advertising agencies and were paid on a pro rata basis, taking care to spend more time cultivating good relationships with the leaders and the authorities at the school. Zeng Hao tended to spend too much time helping his students study and understand art. In an environment that stressed the mechanical study of art history and concepts, Zeng Hao’s work, using contemporary art practice, was interesting. However, in the period when the political system continued to create problems in educational institutions, the concepts of art that Zeng Hao presented to his students were regarded as frankly ‘illegal’, and no textbook contained the information about art that he imparted. However, the real problem that Zeng Hao faced was that the outmoded ideology retained the strength to control all organizations throughout China, including the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, and no signal calling for a change of ideology among bureaucrats was forthcoming from the official side. It was only the market and the issues raised by that market that alerted Zeng Hao to the fact that changes in the prevailing outmoded views about art were inevitable. His dilemma was part of a general conflict, the background presented by the conflict between the historical inertia of the political system and the legitimacy deriving from the market. This contradictory background deprived social life of definite demarcation lines and people could only rely on specific linguistic contexts to make decisions. What was permissible in society (the market domain) was not feasible or legitimate within an organization or institute. An earlier generation of artists had used ‘truth’ as a criterion for discussing art, but Zeng Hao addressed the same question in a different way, appealing to the need for art to express daily life:

We have lived through changes that have affected the entire society. When I graduated from high school the Cultural Revolution had concluded and values began to change. At that time the pace of change in China was very rapid and not incremental; people’s basic values had to undergo a total makeover. When I went to college, there was another total change, and when I graduated from university, everything changed once more. Throughout this entire process of constant change, you were always searching for basic personality criteria. After graduating from the academy, this picture temporarily continued. Then I had to consider what I would go on doing and why I would continue to paint in the way I do. I am only able to paint things I can experience and feel, and whether those things are good or bad is another matter. At least I can feel and grasp things.[8]

At one point he said: ‘You might think I make no sense, but you have to admit I’m honest’. One could theoretically fault Zeng Hao, but he could not be faulted on matters of ‘truth’ and ‘meaning’, even if these two concepts were being constantly challenged by new terms of reference. The terms were being deconstructed by artists in Beijing like Liu Xiaodong, Fang Lijun and Liu Wei, and by the pop artists of Wuhan like Wang Guangyi and Wei Guangqing. What Zeng Hao wanted to express was that there was nothing in the real world that was not worthy of attention, unless it was some desire summoned up in the twinkling of an eye, as he later candidly explained:

A red sofa, a cup lying on its side, a shiny mirror, a healthy potted landscape, half a roll of toilet paper, a clean toothbrush and a person half wrapped in a quilt ...everything is unusually clear. I’m having a piss which cascades in an arc towards the porcelain toilet bowl I stand facing. It’s not too early and it’s not too late. It’s not there or anywhere else, it’s here. Everything is just right, here at this moment. That person pissing is not him, it’s not you, it’s just me.

I like truth and clarity; it’s great that the world is so true and so clear.

In 1997, Zeng Hao held first solo exhibition, at the Central Academy of Fine Arts Gallery. One of the important things about this exhibition was that he sold a work there, and even if his future was unclear, his confidence in the ability to support himself was enhanced, and the income from the sale enabled him to soon rent a house in Beijing. After four years in Guangzhou, it was difficult for Zeng Hao to hold on to his job at the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts and work, so in 1998 Zeng Hao finally left the city. In Beijing’s Huajiadi district he often spent time with his old friend Zhang Xiaogang. Huajiadi in north-eastern Beijing was where Zhang Xiaogang had set up his first studio, and this fringe area on the edge of town was where a lot of drifters from all parts of the country gathered, and it gradually it became a center for artists who came mainly from China’s southwest. From 1983 to 1985, Zeng Hao had worked as an art instructor at the No. 11 Middle School on the outskirts of Kunming, and at that time he often spent weekends together with Zhang Xiaogang who worked as an art designer for the local song and dance troupe. Zeng Hao now found himself similarly inspired in Huajiadi. In many ways life in Huajiadi was more or less an extension for the artists from south-western China of their earlier years together at the Sichuan Academy of Fine Arts in Chongqing; they worked in their studios during the daytime, assembled in a particular restaurant for supper, drank and played cards, often until daybreak. Zeng Hao loved the life style for the freedom he again enjoyed, but, in keeping with his personality, he remained an introspective person of few words.

However, his personality was a problem; his silence and introspection meant that he also needed to ‘break out’ and ‘calm down’. At the beginning, Zeng Hao never thought of his work as being far removed from that of other artists, especially when he was in Guangzhou, but when he began to reduce his figures to the same level as material objects, he felt that he had made a decisive turn. However, once he had made this turn preparing him for future development, he began to confront problems:

I was a fairly self-centered person and the external world didn’t influence me very much. I also wanted to continue doing my works from this stage for some time, until I felt that I was through with them.[9]

Zeng Hao was still arranging small objects in his paintings and Beijing, but more importantly the personal style of his works, now presented him with many opportunities to exhibit. From 1998 onwards, he frequently participated in local and international exhibitions; he should have succeeded in showing people the world through his own mode of observation but they often did not see the questions he raised because of the customary way in which they looked at his work.

Zeng Hao acknowledged the existence of space, but if excessive attention was paid to physical space then it becomes meaningless. He now felt challenged to try and represent objects in the darkness of night. At the outset, he turned off the indoor lighting in his works, as in 12 June 1997 (1997 nian 6 yue 12 ri), in which he placed the source of light outside the windows of this room, so that the cold dull light matched the state of ennui of the seated man. The depressing light in this work may have alerted Zeng Hao to the external world that was the source of the light, and in 1998 he surveyed a cityscape by night, that encompassed the glimmer of indistinct neon signs, in the work titled 29 August 1998 (1998 nian 8 yue 29 ri). To questions related to the meaning, intention and particularity of this cityscape, Zeng Hao simply asked why this night scene could not be made into a painting: ‘In reality, you discover that the life you encounter is unknown to you. Aimlessness, pointlessness and boredom may well constitute the totality of life, as they are such extremely important aspects of our lives’.[10] In Zeng Hao’s view, his own life at least was made up of countless fragments, but the more important question was whether life itself was worth depicting. Given this attitude, Zeng Hao had clearly given up the quest for meaning and truth and wanted to simply tell us that the truth is simply what we see before our eyes. In the past, the flowerpots and other similar objects that Zeng Hao positioned in his hypothetical indoor spaces were, at that time, simply flowers and trees serving as interior decoration and they reflected the arrangement of objects conforming to a particular understanding of reality. But by 1999, Zeng Hao had stepped outside the room and he placed the few natural objects in the city, such as trees, directly into his compositions as subjects, as in the work titled Five AM on 3 April 1999 (1999 nian 4 yue 3 ri zaoshang wudian). Regardless of the titles he chose for his works, the gray-blue tones, the wandering pedestrians and the lonely vehicles within the composition held together by a canopy of trees evoke the aesthetic of the dawn light.

In 2001, Zeng Hao placed one of the planes that fly over Beijing daily as a part of the city scenery in the composition of his work titled On the Afternoon of 4 March 2001, Xiao Li and the Others Went Out (2001 nian 3 yue 4 ri xiawu, Xiao Li tamen chuqule). The artist was, in fact, now using random and casual material from his daily photo shoots, and these scenes captured in an instant, whether clear or fuzzy, were part of his true visual world, his idea being that the truth is never whole, its existence revealed only through details. Zeng Hao accepted this rationale, the plane later becoming a regular feature of his works.

From 2004 onwards, Zeng Hao began placing his scattered falling objects, such as wardrobes, mineral-water bottles, fly swatters, sofas, desks or rolls of toilet paper, in scenes of dawn or dusk, as in the work titled 23 June 2004 (2004 nian 6 yue 23 ri), and in works like this, the scenery is concrete and seems to have been casually photographed. However, the relationship between the once scattered falling objects and the scenery still remains fluid, and the artist continues to remind us of the uncertainty of space. But, regardless, until 2006 those works in which the concrete environments and objects make reference to photographs more or less reveal the artist’s need for a reality with warm elements, as in 7:30 PM on 13 September 2004 (2004 nian 9 yue 13 ri, xiawu 7 dian 30 fen), and even if we look up to see a plane high above, there are soft white clouds around it. The artist now seems to be trying to tell us that he knows that space exists, and it is even beautiful. But his indoor scenes finished in 2006 still feature scattered odds and ends and have no center, but the atmosphere is much more gentle and tranquil. In 2007, human figures again become subjects in his compositions and the artist now seems to be telling us that nothing has changed, allowing us to catch up on the latest look of those people who once transformed into and functioned as material objects.

In 2006, Zeng Hao also reproduced the objects that he had depicted in his paintings in various materials and placed them in three-dimensional installations, even including the buildings, the planes and the brassieres. Usually he placed these sundry objects in transparent spaces, evoking the architectural design called the It Room (Ta wu) that Zeng Hao completed in 2004, for which he provided the following explanation:

The It Room villa is enclosed in a box constructed from shaped steel and transparent glass. The rooms chaotically weave their way through the box. The rooms and the space seem unreal and completely empty, and are intended to construct a sense of fragility and unease. This villa attempts to convey the uncertain relationships that exist between people in contemporary society and the environment, constructing a lonely and estranged atmosphere that allows people to re-experience their own meaning.[11]

Because of fears of exceeding budget estimates and future operational costs, the construction of this building did not conform to Zeng Hao’s original plans and from the three-dimensional design we can see his particular unique concepts of space design.[12]

At the end of 2006, Zeng Hao staged his solo Looking Around exhibition in Shanghai.The exhibition featured a toilet roll installation and a two-in-one space; a green interior and the surroundings of the Three on the Bund gallery space. In this solo exhibition, Zeng Hao expressed his concept of space and environment through a real physical space without modification; the city that the artist offers is in fact naturally fantastic. Most importantly, the toilet roll, which is a constant element in his paintings, was now enlarged and on it was recorded news and gossip from around the world as well as personal graffiti; the artist was making the point that toilet paper can simultaneously wipe away important and unimportant issues - private, public, ethnic, political and global. In this way, Zeng Hao was presenting a specific narrative while expanding the scope of his artistic language.

Zeng Hao’s art began forcefully then later the natural instincts of his paintings seemed to be aroused by reality; when he discovered art’s own significance he quickly looked for channels to break through barriers. He almost instinctively rejected the expressive stance of modernism and relied on his sensitivity to rapidly abandon any idealistic expectations of essentialism. In seriously confronting his own life, he placed very little reliance on ennui or absurdity. The critic Huang Zhuan has discussed Zeng Hao’s uniqueness:

Zeng Hao is not a ‘problem’ painter in the strict sense of the term. Compared with Zhang Xiaogang, his works seldom have that deep historical sense and authentic culture to narrate. And compared with Shi Chong, his works do not set up obvious questions or rely on extreme techniques, but his works draw uniquely on a new spiritual reality with introspective character and psychological elements that came in the wake of the pretentious cynicism (quanru-zhuyi) and nihilism of the early 1990s. Yet the contradictory narrative structure and pictorial mode totally match this era in which we have lose our authenticity for the very same reasons, and so, for these very reasons, I regard Zeng Hao as a representative painter of the Chinese conceptual painting movement of the mid-1990s.[13]

Li Xianting has described the ‘heightened conceptualization’ of Zeng Hao’s art as linked to and comparable with the position of Cynical Realism: ‘The appearance of Cynical Realism signaled a conceptual change in contemporary art, abandoning the superior realist posture adopted by the two generations of artists on either side of the Cultural Revolution, and for the first time artists were looking at the reality around them from level ground. Mediocre, dull and accidental snippets of daily life provided the basic language for Cynical Realism. It was simply the political background of the time that cast them as ‘punks’ (popi) in their descriptions of segments of mundane life’. [14] But Zeng Hao contained the ‘mediocre, dull and accidental’ within the range of his style, and while his paintings appear insignificant, it is this very insignificance that provides a special narration of this time of change; his paintings provide a casebook for examining the history of contemporary art in this period. Compared with images that are exaggerated and massive in scale, Zeng Hao’s works achieve his unique expression in an ordinary manner and without exaggerated language, even treating the titles of his works casually, yet his starting point and attitude are absolutely accurate:

His titles accurately pinpoint particular moments in time and this seems to confer a special meaning on his works. They capture important moments in life, determining decisions about life, working opportunities or major events. Yet at the same time they might be moments in a meaninglessly repeated and constant time. For everyone, life is almost always constant repetition of this kind.[15]

Zeng Hao here drags the basis of life back to the fundamental fact that, in confronting death, everything is equal. This is tantamount to saying that if we define human history then it is not only the times of heroes that are important. Zeng Hao knows that in this day and age the concept of the hero is basically unworkable and also inappropriate. As an artist who is sensitive, patient and resolute of will, Zeng Hao is naturally not denying the renowned events and heroic feats of history, but he makes the following point:

What can an individual do? In fact it doesn’t matter. What is important is constantly repeating those daily things that determine your entire life.

The art that resulted from Zeng Hao’s way of thinking serves as a micro history recording daily life, and this pictorial history sets him apart, at an utter remove from false and mighty narratives and cynicism that shirks responsibilities.

NOTES:

[1]‘Art Is Only My Lifestyle: Interview with Zeng Hao’ (Yishu zhi shi wode shenghuo fashi).

[2] Tang Xin ed., Huajiadi: Record of Personal Conversations with Those Involved in the Development of Contemporary Chinese Art, 1979-2004 (Huajiadi: 1979-2004 nian Zhongguo dangdai yishu fazhan qinshenzhe tanhua lu), Zhongguo Yingcai Chuban Youxian Gongsi, 2005, p.72.

[3] Wang Jing, “Secrets of the Room’ (Fangjian li de mimi: Zeng Hao fangtan), in Oriental Artists: The Masters (Dongfang yishu: Dajia).

[4]Ideals and Operations (Lixiang yu caozuo), Chengdu: Sichuan Fine Arts Publishing House, 1992, p.168.

[5] Wang Jing, op. cit.

[6] Tang Xin, op. cit., p.129.

[7] Wang Jing, op. cit.

[8] Tang Xin, op. cit.

[9]‘Art Is Only My Lifestyle: Interview with Zeng Hao’ (Yishu zhi shi wode shenghuo fashi).

[10]Zeng Hao, My Life up to Now (Shenghuo gua dao xianzai).

[11] The Helanshan Houses: Thought and Works (Helanshan fang: Sixiang yu zuopin).

[12]Zeng Hao’s designed buildings almost all had see-through glass walls, and so were not regarded as energy efficient for either summer or winter conditions. This was especially the case of his houses designed for the Helanshan District which is very subject to intense sunlight.

[13] Huang Zhuan,Psychological Portraits from the Consumer Age (Xiaofei shidai de jingshen xiaoxiang).

[14]Li Xianting, ‘Ordinary but Remote Scenes of Daily Life: Zeng Hao’s Works and Related Topics’ (Pingmian er shuli de richang jingguan: Zeng Hao zuopin ji qi xiangguan huati).

[15] Record of Interview with Zeng Hao (Zeng Hao wenjuan huida).

Friday, 1 February 2008

Translated by Dr Bruce Gordon Doar